The industrial cities could only exist because they were fed by the countryside that pursued agricultural innovation over hundreds of years. Both the industrial and agricultural revolutions began, by the way, in the monasteries. This is not the world the technocracy wants to restore. It does not want you to know the history. Technocracy aims to supplant the old priesthood. Technocracy has magic …

The cryptocracy, at its simplest, is the observation that the elite empower themselves by hoarding knowledge in order to rule, and denying it to those they control. In the same way, the elite schools today still teach the classics, the philosophers (especially Plato) and techniques of government (cybernetics) down the ages, giving their children the mindset of ruler. They believe in knowledge for them and ignorance for the rest. The translation of the Bible into the vernacular shattered the authority of the religious priesthood …

The rulers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries fought hard for their influence over the flow of information just as today. Bills to censor and shadow-ban content on the basis of online “hate” (undefined) have been passed in Australia, are in the parliamentary committee stage in Britain and are being considered in the U.S. and Canada. The elite of the Enlightenment worked hard to kick away the ladders and keep the populace in their place …

The ruling class never abandoned the complete sphere of knowledge. They just constrained the rest of us and introduced the concept of specialization. Education was narrowed to the needs of the job.

— Moneycircus blog, Occult Capitalism Or Last Exit To Utopia — The Great Reset: a prelude (2021)

This is Part II of a three-part transcript of a conversation between Alex Thomson senior and Alex Thomson junior on the heritage of literacy in the English-speaking world. Part I is here.

Alex sr: So we go on [in my historical survey of British and American literacy rates], and the high point is the Baby Boomer [coming-of-age] year, 1963. Nominal [full] literacy of 99%—call it 100%—was achieved in 2003 in the West, in Britain. In America, it was just a couple of years before that. Basically, we’re 100% literate now as a nation.

Alex jr: You alluded there to 1963, because that was the end of the steep growth. Britain—the whole Western world—started plateauing in intellectual level at that point.

Alex sr: There is a book [about the remarkable changes that took place that year]. And I remember it. I was sixteen then, and I specifically remember, in 1963, on my sixteenth birthday, going round about, walking in the hills, and realising that my own culture had shifted. I realised it. I couldn’t have articulated all of it; but I realised it.

Alex jr: You were up in the Ochil Hills, but people could feel it in London and New York just the same. A poet of the age, Philip Larkin, mischievously said that sex was invented that year. Of course, he meant it was commercialised that year. And you could feel the shift in the atmosphere?

Alex sr: There is a book [that traces the crucial changes of 1963], and I’ve got it: That Was The Year That Was.

Alex jr: The title is a skit on That Was The Week That Was, the first of a new-style [genre of] irreverent BBC comedy that came on [television at that time]. We now understand that what the BBC was up to was easing the way to post-literacy.

Alex sr: And I mark that year also because in 1962, the first modern one-volume Bible commentary, Peake’s Commentary, was issued: a very famous commentary. And in 1963, the second edition of Hastings’ Dictionary of the Bible was issued.

Alex jr: So these are the fruits of the previous generations, distilled down to a common man’s single volume: “Here you are, you’ve got it all. You’re standing on the shoulders of giants.”

Alex sr: Yes. And so you can pretty well mark it: 1963, for me, is the watershed year, the tipping-point.

Alex jr: And so a man of your generation in his youth, if he was well mentored—either by privilege, or in your case by being adopted for tutoring purposes, as it were—had everything he needed: he had no requirement particularly to go to university, although many did.

Alex sr: No, he didn’t [need to go to university]. That’s exactly right, yes.

Just to note that in 1963, the US Supreme Court banned mandated Bible reading in publicly-funded schools, and by 1967, Bible reading had more or less ceased in UK schools. When I was at school, we started every day with a Bible reading and the Lord’s Prayer, and so forth.

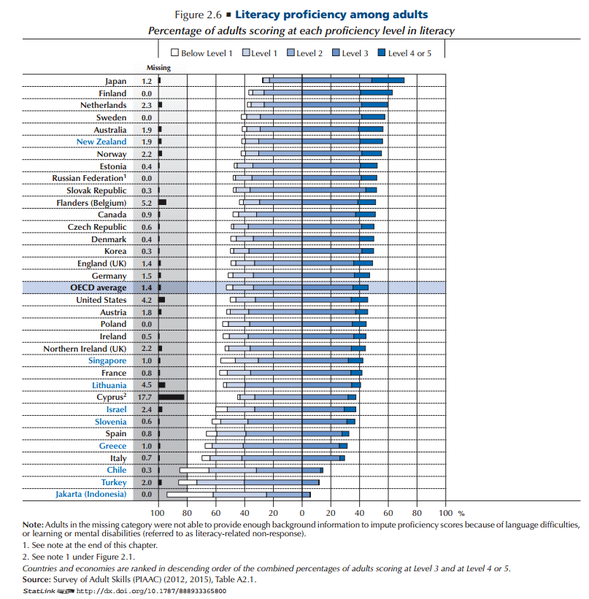

There is the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which is a United Nations [observer body], a [largely] European thing. The OECD does a thing called the Pisa Report, named after Pisa, Italy.

Alex jr: It’s meant to benchmark the performance of the workforce and the future workforce, i.e. school pupils, of all the most developed economies.

Alex sr: Yes, and adults as well. Every three years—2009, 2012, 2015, 2018—[they conduct a literacy study]. They didn’t do it in 2021 because of Covid; it’s going to be done next year, apparently. It just shows that out of the 65 to 77 countries that take part—more, latterly—both the US and the UK are just average. That is shocking.

Alex jr: Yes, and the great grief to you is that Scotland, since devolution [the setting-up of a Scottish Executive in 1999], has utterly plummeted [in literacy], and it’s become a national scandal, to the extent that Scotland’s most recent OECD report was withheld. And it’s not just one party, but the SNP is in the lead here; it was happening under Scottish Labour-run devolution as well, pre-2007. The civil servants were deliberately reframing the curriculum into something called the Curriculum for Excellence [since signally rebranded the “Curriculum for Scotland”].

Alex sr: But it’s happened in the States [with Common Core]. In terms of literacy and numeracy, the US and the UK are consistently at or very near the bottom of the international tables [of first-world countries].

Alex jr: And we’re not [even] comparing ourselves here with extremely bright, numerate East Asians; we’re talking about how we perform vis-à-vis Italians, Finns, Hungarians.

Alex sr: Exactly, yes. And we’re [merely] above average, getting about twelfth and thirteenth [places] out of 77. That’s terrible for two countries that are in the top five economic powers of this world. It’s terrible.

Alex jr: The point is that at the current state of decline in Scottish education, the authorities—not just at political level, but the bureaucrats—will no longer release the reports produced by the OECD, because it would reveal a precipitous decline.

Alex sr: No, they won’t, no. I’m doubtful whether Pisa 2022 will take place, actually.

Alex jr: And this is a theme you’ve discovered in other ways, as well: to get accurate statistics on literacy is increasingly difficult.

Alex sr: They don’t like to [disclose them]. And they don’t like to discuss them if you do get them.

I should just point out that whereas in the early days, you had to add for Bible oracy, you now have to subtract.

Alex jr: Because there are people who officially can read, but you ask them to string a sentence together on paper, and they can’t.

Alex sr: And amongst Christians, now, for example, in 2021, the best estimate is that reading literacy is 99%, [so] nominal 100%, but I would deduct 45 percentage points from that to arrive at 54% effective Christian literacy.

I would say that barely half [of British Christians are literate]. Even the Bible reading, or—how can I put it—more-than-nominal [Christian population] is only barely literate now. Bible-literate, I mean.

Alex jr: They were saying as recently as around 2000 that it was about 15% in Western countries that was functionally illiterate. You’re suggesting that’s tripled in one generation.

Alex sr: The deductions that I’ve made are:

1963: -5% [from the nominal 100% British literacy rate to account for functional illiteracy];

1967, the Baby Boomer [graduation] year: -10%;

2003, when we got nominal 100% literacy: -20%;

2011, which was the four hundredth anniversary of the King James Bible: -30%;

and [in 2021], on current trends in data: -45%. [N.B.: This closely matches Australia's nationally-averaged functional illiteracy rate of 47% as of a decade ago.]

Alex jr: So, if you follow that demographically, that means, effectively, statistically, that no young people coming out of school are properly able to read now.

Alex sr: That is one of the inferences, definitely. Definitely, definitely.

Now, I've got a page here of the Pisa results: four of them, 2009 to 2018. It just shows you basically where we are. The US and UK are twelfth and thirteenth in the ranking, which is terrible. Pisa also does a thing called the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC).

Alex jr: This is putting a polite spin on it, but it’s asking people from shelf-stackers to crane drivers whether they can read well enough do their jobs, isn’t it?

Alex sr: Right, and it knocks the results into five levels, one to five. Category 5 is university/college level; 4 is Proficient; 3 is Intermediate; 2 is Basic; and then 1 is subdivided below Basic.

Alex jr: This sounds like the euphemism that you had as a schoolteacher: if you couldn’t say anything about a child’s performance at school, you would write, “Johnny is working towards attaining Level 1.”

Alex sr: That’s exactly right, yes. And, basically, our Bible reading is at Level 2, which is the level needed to cope with everyday tasks. One-third of US and UK Bible readers are at Level 2 [basic reading ability], which accounts for the fact that our modern Bibles are really sub-literate. I wouldn’t say they’re aliterate [written so as to assume a profound inability to read], but, you know, they’re not really what they should be. Of course, we’d get shot for saying that.

But if you think that blockbuster novels are [deliberately] set at a reading age of twelve—that’s [books intended] for adults as well …

Alex jr: … And I was talking to a Dutch journalist, a quality one, just last week—[who writes,] in fact, for a Christian title. He said—with some considerable pride—“I am skilled in writing for twelve- to fourteen-year-olds.” They think that that’s the [desirable] standard of their profession now.

Alex sr: Yes. Popular newspaper text is [deliberately] set at reading ages nine to eleven, but their editorials are set at reading ages eleven to fourteen. If you read an editorial in any newspaper—even a tabloid, a low one—the editorial is always at a higher level.

Alex jr: Oh, yes, they use better words.

Alex sr: But the tolerable limit for any reader can be taken as two years above the nominal year.

Now, that means that the people [about whom it is dismissively claimed,] “Oh, they can’t read very well, they wouldn’t understand that [word]”, if you spent time with them—that’s the key!—they could increase their reading age by up to two years. Easily.

Alex jr: Which, of course, you deny if you go with “the soft bigotry of low expectations”, as is the set phrase now.

If you say, “This racial group, that educational group, will never read beyond fourteen-year-old level,” and if you therefore never put, as it were, sixteen-year-old words in the text [that they are set in their schooling], then you are condemning them to [reading only] thick writing.

Alex sr: Yes. So any teacher should look at a group and say, “Whatever their reading age, I can, in time, put it up by two years.”

Alex jr: Is there an incentive [to raise pupils’ reading age]? I know that a good schoolteacher wants that, and has that incentive, and a good parent does.

Is the system, or the Establishment, incentivising this idea that [reading ages can be boosted] with a bit of attention? Because we hear a lot [in education journalism] about extra attention [at school]; it was a big thing in your native Clackmannanshire for a while, with new-style [teaching of] reading.

To be very honest about the Establishment, is it interested in pushing people to read better?

Alex sr: No, is the short answer. No. In very few cases.

I think there are only two categories of people in our culture who are interested in improving their reading. The first one is definitely serious Christians. They want to push other people to read their Bibles.

Alex jr: Particularly, but not exclusively, Protestants, because it’s a persuasion which is based on preaching and study of the Word.

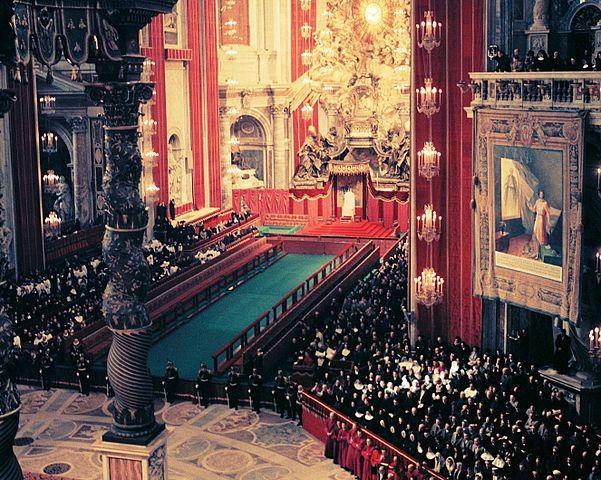

Alex sr: But I have to say that there are Roman Catholics who have caught up—not catching up, they’ve caught up.

Alex jr: Most definitely. Since the launch of the New Jerusalem Bible [1985], whose original edition was French [1973], but we have English versions [of it] now, [Roman Catholicism]—[in fact,] since [the Second Vatican Council in] 1962—assumes greater literacy.

Alex sr: Whatever we think of their theology in places, there is no doubt that there’s a great desire, a genuine desire, on the part of many of their clerics—good men—to have their own people read and understand things.

Alex jr: And likewise the Muslims.

Alex sr: And the other [category of serious readers today] is the remaining diehards in universities—real universities—who actually want students to learn and enjoy culture and the rich heritage that we’ve got.

Alex jr: Jeffrey Hart at Dartmouth College wrote Smiling Through the Cultural Catastrophe: Toward the Revival of Higher Education, and he’s a good example of the Ivy League version, but you have that in Britain as well. Some of them are slightly flamboyant personalities, but the big-name academics who don’t want just to manage decline seem to be clubbing together, and de-facto forming a new academe outside the system for this purpose. A sort of living-room-based academic setting.

Alex sr: Yes. Now, one of the things that I did was, for 2011 and for 2014 and 2017, I had access to a couple of datasets by the American Bible Society, [and] Indiana University-Purdue University’s Bible survey (IUPUI), as well as our own independent one, and compared the bases of them.

Alex jr: Again, you used American statistics because the British ones are not readily available.

Alex sr: No, no. I had other ways of [getting hold of British statistics], which is difficult.

Alex jr: But it’s the same whenever you write to British publishers—Christian or secular—[asking,] “Can I have your stats?” “Who are you?”, [they reply.] Americans are a bit more open about this.

Alex sr: Well, the Brits have never published them, [but] since 2017, the American Bible Society has ceased publishing the statistics for preferred Bible versions. It won’t tell us. And I’ll explain you the reason why.

Alex jr: This would be the tell-all, wouldn’t it? You can frame the question cleverly, but if you go about it neutrally—if you ask someone, “What’s your Bible of preference to read?”—what they don’t want to hear is people saying, especially in America, “King James.” There’s lots of shades of King James [Bible on the market now], but they don’t want to hear that. They want to hear something that can be commercialised.

Alex sr: Here, [I have survey responses from] 1993, 2011, and then 2014, 2017, 2018, 2019 [and] 2020.

Let me give you 1993. I’ve done two sets for the US and one for the UK. In 1993, this is the answer among serious students [to the question] of preferred Bible version.

So this is what you and I should be [interested in]; we haven’t got time or resources to concentrate on everybody. If we have a serious mission in our declining culture, it’s to encourage serious Bible reading among serious students. We cannot hope to stem the whole tide of cultural decline, but what we can do is to make sure that those who are [interested] are able to hold the knowledge until some common sense comes back into culture.

Alex jr: Yes. Many of the people who come knocking on UK Column’s digital door say, “I came here because of a sense of disquiet on behalf of myself or my grandchildren.” One of the things that a section of the audience says is, “Can you direct me towards a good Bible that I can base my cultural thinking on, and good resources?” So you’re talking about this remnant, really.

Alex sr: Yes. So, in 1993, 59% of people [surveyed in this category] preferred the King James, [and] 5% the New King James. So that makes, in inverted commas, “the King James tradition” 64%.

Alex jr: The “King James family of Bibles.”

Alex sr: Because sometimes, people use both [the original King James Bible and the New King James Version]; sometimes, they confuse in their own minds which one [they should call their preferred version], because they use both; and sometimes, they just get mixed up.

Alex jr: The New King James is basically [a text in which] the thou’s have been changed to you’s.

Alex sr: And, for example, the Indiana University-Purdue University study didn’t initially differentiate. It came to 55% for the AV, and I contacted them and said, “Where’s the New King James?” They said, “Oh, yes, it will be in there.”

Alex jr: So it was lumped in with “King James”.

Alex sr: But—now this is the interesting thing—the NIV at that point was 8%; the ESV [English Standard Version] didn’t exist. So you can say that the top four—the top three, because the ESV [didn’t yet exist]—accounted for 72% of serious Bible reading in America. In the UK, it was 71%; very near.

In 2011, the year of the NIV’s [major new edition] …

Alex jr: … and of the King James quatercentenary …

Alex sr: … [it was] 51% KJV; 11% New King James, [making] 62% KJV tradition; 12% NIV; 4% ESV. [That makes] 78% total [for the top four].

Alex jr: So, for those who are new to this subject, shall we say that the globalist, or revisionist, Bible of choice for the Western world, for the English-speaking churches, had failed to make even a small dent in [serious Bible readers’ preferences]?

Alex sr: Yes! I’ll give you the 2020 [figures]. In the US, the AV has dropped to 35%, but the New King James is at 16%, so that’s still 51% King James tradition. The NIV is 9%!

Alex jr: So it’s dropping off, even.

Alex sr: It’s dropping off. It was never very high among serious Bible students. The ESV is 17%, and the total [for the big four] is 77%.

Alex jr: And the ESV is the latest revision of what was originally the Revised Version [1881], and the whole point of that [ESV] is that it is a more linguistically and theologically conservative way of modernising the Bible [than the NIV represents].

Alex sr: So, apart from the NIV, you can say that 68%—almost 70%—of serious Bible reading is in the King James tradition, still!

Alex jr: And not all of our listeners would go this far, but there is a school of thought that calls the NIV a New Age Bible version, and that points to its use and the pushing of it by the megachurches, and behind them were figures like Peter Drucker, who was a management guru. The slogan of this lot was “creating community”: the idea that if you can all read the same dozy Bible, then you can all be led more easily.

Alex sr: Well, the men of the nineteenth century—largely Anglicans, but also Nonconformists—said, “There are faults and infelicities in the Authorised Version; we’ve got to revise it; but we don’t want to do anything to destroy our common version”, as they called it.

Not even the most radical of them wanted to get rid of it! What they wanted to do was to slowly, gingerly, carefully revise [its few shortcomings], by opening up a second margin or expanding the existing margin, and seeing how things [were accepted] over time.

Alex jr: As late as the Bible studies in the 1950s by Dr Martyn Lloyd-Jones, where he went especially through the Epistle to the Romans (it was the mid-1950s and it was fortunately tape-recorded and is now available online), in almost every one of those little lectures—about one lecture per verse, very intense—he says at some point during the lecture, “Now, this is not the best way to translate it, what we have in the King James. The Revised Version is a slight improvement,” he often says.

Alex sr: When I was younger, amongst Scottish Baptists and Scottish Brethren, you read nothing in public but the Authorised Version.

Alex jr: Because it was the common version, the [public] reading version.

Alex sr: But as frequently as you wanted, you often referred in your preaching or teaching or explanation to the Revised Version. And that was quite acceptable.

Alex jr: And there’s another layer to this, because in the first half of the twentieth century, from about 1900 to 1950-ish—certainly in Scotland and more generally in Plymouth Brethren circles—it was the expectation that anyone who was taking a service, so shall we say a lay brother leading the service, had consulted the Hebrew and the Greek.

Alex sr: Yes, yes.

Alex jr: Not just a minister.

Alex sr: No. That’s a whole other game, about working-class men in Scotland and other places teaching themselves Hebrew and Greek, encouraging each other.

Alex jr: What did you find in Crewe once?

Alex sr: When, in 1969, the Easter before my Finals, I was down staying at my fiancée’s—my now wife—I discovered to my horror that I had forgotten to pack my large Greek lexicon, which is absolutely essential for revision. So, in a panic, I went to Crewe Public Library, thinking, “The best I will get is they can maybe get me an inter-library loan somewhere.”

And fortunately, there was an old man there, providentially, and I said, “I’m in a panic,” and he said, “Come with me, young man.” He took me down the stairs, and he said, “Look up there.” And there was, not the biggest one, not the small one, but the nice middle[-sized Liddell & Scott’s Greek Lexicon.]

Alex jr: The “Middle Liddell.”

Alex sr: The “Middle Liddell”, which was adequate for my purposes. And I said [in a tone of amazement], “Where did this come from!?” He said, “Look inside.” I opened it up.

It said “Crewe Mechanical Institute and Working Men’s Club” on the page stamp. Expunged [from their collection] just before that.

Alex jr: So in England’s largest railway town, the very definition of the plebeian working class in England, the working men had clubbed together to study the Greek New Testament!

Alex sr: I said to him, “Where did [the interest come from]?” He said, “Well, that would be Christian Brethren.” Mostly Brethren. It would be Christians [who wanted to acquire a Greek lexicon], but mostly Brethren.

Alex jr: Yes. People need to bear this in mind when they make this claim that the King James Bible “is fables”, “isn’t based on the sources”, or whatever: that people [who made use of the King James as their English Bible] were checking the source languages themselves.

Alex sr: They were checking the source. They realised [what needed revision].

But also, they knew perfectly well that if you came across a passage [Proverbs 30:26] saying, “The conies are but a feeble folk”, and you think, “What’s a cony?”, [and] the RSV [changes it to], say, “The rock badgers,” or, “The honey badgers,” or whatever it is: what’s [the gain of twiddling with the word]?

There’s not much gain in actually getting it right. People understand [in the King James Bible, from the context] it’s an animal that lives in the rocks, you know! So there is that sort of [exaggerated concern about supposed technical inaccuracies].

And also, the other thing is: if I say [in the KJV], “He entered the city,” and you want to put a new Bible out, you’ll say, “He went into the city” [for the mere sake of differing visibly]. And if I say, “He came out,” you’ll put, “He exited.”

Alex jr: As a professional translator and interpreter, I know [and have written on the matter: Part I | Part II] that a large part of the game when you’re called in to revise or supervise someone else’s work is needlessly fiddling with synonymous words and expressions, to give the client the impression that you’ve done a decent job.

Alex sr: Yes.

So just to [finish that off]: in 2020, in the US, 77% of [serious] Bible preferences were for these four [versions]: KJV, New King James, NIV, ESV. And in Britain, the same.

Alex jr: So the New International Version achieved effectively zero popular acclaim in the churches?

Alex sr: Well, it’s in the top four, but it’s the lowest.

Alex jr: But that’s not saying much, is it, because you also went on to find how the NIV got the sales.

Alex sr: You cannot get these figures for the UK, but for the US, the Evangelical Christian Publishers’ Association (ECPA) puts out, each year, US Bible unit sales and dollar sales.

It’s the unit sales we’re interested in, and I’ve got them for 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020. And consistently, the NIV is first on the sales [ranking].

Alex jr: And this allows them to trumpet, “America’s best-selling Bible!”

Alex sr: And usually, the King James is next.

Alex jr: And then the New Living Translation, which is very chatty.

Alex sr: It used to be the ESV [in third place], but the NLT’s got a few more sales each year, and the ESV is fourth. Then, fifth, New King James, and so forth.

Now, what they then can tell you is that “the NIV is the bestseller in America”. Now, that is true; but it’s true because the sales are registered in America, but many of the Bibles go abroad to be read.

Alex jr: Particularly, they’re foisted upon Africa, aren’t they? English-speaking African countries.

Alex sr: I don’t know; I haven’t looked at the mechanics. It may be that [the NIV publisher] in America sells to a registered company in America that then sells to companies abroad. But the first sale is registered as an American sale.

Alex jr: So they’re effectively international distribution Bibles.

Alex sr: I think so. International distribution is important.

The other thing is that the KJV in these figures is understated. Why is it that there’s this clash between what people [give as their] preferred Bible and the NIV [sales figures versus] the KJV? Because many of the NIVs are read abroad: they’re sold in America, so they top the sales list, but not the [list of] preferred versions, because they’re not read in America.

The King James will not top the sales, but will [nevertheless] top the [ranking of] preferred Bible version, because many organisations print and publish the KJV without registering it through the Evangelical Christian Publishers’ Association.

Alex jr: Take Brian Gerrish, and he’s certainly not a rarity. I’ve visited his home enough times: he’s got two or three King James Bibles. Not one of them will ever have registered in modern sales figures, because they’re family possessions, but he still reads them.

Alex sr: But the Such-and-such Brethren Association, or the Something Missionary Society, will [still] get [the KJV] printed [today]. They can get it printed in India or China, or wherever.

Now, this takes us back to the history of things, and this is rather interesting. Basically, what we’ve said about Bible versions is, we’re conned with the information. Don’t be alarmed; there are only four versions [of importance], and, by the way, it looks from recent figures as if the NLT is about to overtake, and probably has already overtaken, the NIV.

Alex jr: This is the New Living Translation, which makes the NIV look conservative by comparison! It’s awful.

Alex sr: [The NLT] certainly seems to be competing with the NIV, and maybe overtaking it. So it will be interesting to see.

Alex jr: So, if we combine that with your previous remarks about nearly half of the West being functionally illiterate, what this means is: if you can’t cope with the KJV, then you can really now only cope with a “Hey God!” version.

Alex sr: I am doubtful whether this exercise can [ever] be done again, because you cannot now get, in the public arena, some of the information we got. And this cost the Americans [who commissioned me] quite a few dollars to do, to get information. But they’ve got it all. It’s there. Anyway, when the bomb drops—cultural bomb, or actual bomb—they actually do have a secure place in America.

Alex jr: And not even you know where it is, but you know it’s a hardened facility.

Alex sr: I don’t want to know. I don’t actually agree with them theologically on some things; they know that; that’s not the point, though. The point is, it’s not that they want to be anonymous; they want to just keep the lines of communication fairly tight. And quite rightly.

Alex jr: You’ve had this previously in life, in the studies you did after graduating from St Andrews. Dotted around the European Continent, and I think in some regards in Britain as well, you have found groups of, shall we say, educated laymen who, for theological or just general political purposes, want to do their study in a low-profile way.

Alex sr: Very much so. I am pretty sure that’s the same in America. I’m pretty sure that, dotted around this planet, there are quite learned Christians who just keep a very low profile, and some of them who deliberately have not gone to universities, either.

Alex jr: Particularly since 1992, when—under a supposedly Conservative government, and you were up close and personal with this; you saw it happen and tracked it—the policy decision [in Britain] was that every polytechnic would be called a university.

But, by the same token, if you were not system-aligned, and you were perfectly legitimate and wished to issue diplomas, you wouldn’t be able to call them degrees any more. The discretionary power [to let independent institutions grant degrees for demonstrably good study] was nixed by the Department for Education back then.

Alex sr: And the rot set in to countries that were traditionally very liberal [in the sense of non-controlling in government policy], including places like Switzerland, where extreme pressure is [being] put on people.

Alex jr: Even though they’re not supposed to have a federal level in education, it turned out they did!

Alex sr: Yes, to get rid of the unwanted [non-state-aligned institutions].

Alex jr: What does this tell us? Because we are aware that, for example, the Germans and Americans pressurised Switzerland very heavily [in the past decade] to stop tax loopholes, and to disclose tax information, but a similar kind of commercial or political pressure seems to have been brought to bear on Switzerland in the same era to “jolly well close your education loopholes and stop letting these dissidents educate themselves”.

Alex sr: If you, say, want to practise as a lawyer in Switzerland, you have to have a state-approved degree from an approved institution, either in or out of Switzerland.

Now, the Swiss traditionally took the view—and, in theory, they still take the view—that you can study law and know law and come out with very good degrees from non-registered, non-accredited universities. They are not saying they’re rubbish; they actually say they recognise that some of them were very good universities.

Alex jr: So the Swiss equivalent of UK Column could set up a law school for the defence of the common law.

Alex sr: They could try it, [but] I’ll tell you now that there will be pressures put on you!

Alex jr: Yes, of course.

Alex sr: One of the things that we’ve [found]—I won’t go too much into this, but the university that I was involved with in Europe, put it that way: we lost students because on the Continent, fees for students at state universities have been low. A private university has to charge higher fees to get decent people to teach [at it].

Alex jr: And, in fact, many of the Continental countries mandate that if you’ve passed your school leaving exams with a certain mark—even in vocational subjects with fixed numbers of admissions [numerus clausus] like Medicine and Veterinary Science, pace that requirement—if you’ve passed your school leaving cert with a decent mark, you are entitled to tell University X, “I am a citizen; this is a taxpayer-funded university; you must have me.”

Alex sr: Yes. And [we] also [haemorrhaged enrolments] because the state universities everywhere, in the whole of Europe—and probably the world, with few exceptions—have actually gradually dumbed down their degrees, but some of the private universities, like [the one] I was involved in, refused to do that.

Some Christians said, “No, we’re not lowering our standards.” So we lost students, because students said, “Well, I can get an easier, cheaper degree somewhere else.”

Alex jr: People often kidded themselves, in the half-century now since you’ve left St Andrews, that these pleasant, sleepy places like St Andrews would see the worst of the cultural wastage pass them by. What do we find out this week? St Andrews has gone so woke that you won’t even get on a university course—any of them that you [want to] matriculate in—unless you sign an undertaking that you personally bear guilt for past injustices!

Alex sr: That’s the end of free speech at St Andrews. I would say to anybody now—it tears my heart to say this—“Don’t go to St Andrews.”

Final instalment forthcoming:

Part 3: How we can teach ourselves to read again