So-called education can be used to produce slaves, soldiers and snobs, as well as gentlemen … You can Bolshevize people by education, or you can make them into the perfect Nazi. Unless the intended victim has trained himself to think for himself.

— Thomas Thompson, Lancashire for Me (1940), pp. 22, 25

In late 2021, UK Column's Alex Thomson recorded a one-and-a-half-hour discussion with his father, which is embedded here as an audio upload. That discussion has been turned into three transcribed segments of half an hour each, which in turn concern the 'why', the 'who' and the 'how' of dissidents who educate themselves without waiting for directions from the Establishment.

The project that Alex Thomson senior refers to was produced for an underground cultural preservation body and is not available for public dissemination, but he discusses here the key findings and statistics from it.

This podcast and transcript should be considered in conjunction with the work of the late New York State Teacher of the Year (1991) John Taylor Gatto and the former U.S. Department of Education senior policy advisor Charlotte Thomson Iserbyt. The preliminary matter to Pollard gives a particularly full account of the history of English Bible translation, covering the details sketched below.

Alex jr: I’m looking here at a folder that you’ve put together, Dad, and it’s called The Serious Student Project.

Alex sr: Yes, I’ll tell you about that. I cannot tell you about names too much—I’m sworn to secrecy and commercial confidence and all that sort of thing—but basically, some years ago, a group of Americans, and one or two interested British people, realised that Western culture was in jeopardy, as they thought. The Americans described themselves as being “neither rich nor poor but comfortable”, and “not socialist or redneck but moderate and conservative”.

Alex jr: Ideal low-key dissidents; they had some means and some time.

Alex sr: Ideal, yes. They’re not ‘fundies’; they’re not independent fundamentalist Baptists—some of them may be—but they’re basically conservative evangelical sensible businessmen.

Alex jr: Concerned Americans?

Alex sr: Concerned Americans, and Brits, yes. They saw the way that their culture was going—things were being destroyed and lost—and also how digitisation is destroying things, and they decided that they wanted to preserve not intellectual culture, nor low-brow rubbish, but they wanted, bluntly, unashamedly, to preserve, really, middle-class Western Christian values. You know, the decency and the production …

Alex jr: All the stuff that started getting mocked in your student days by the television characters.

Alex sr: Yes, basically. All the things [about which] everybody says, “If you have that, you must be a hypocrite.” Also, there were one or two other influences, like the change to modern Bible versions, especially when the New International Version (NIV) came out.

Alex jr: A broader section of the audience will be interested in this than our regular churchgoers, because they understand that the Bible is the foundation of values.

Alex sr: The [original] 1978 NIV really started it. And then, of course, when it came to the [major new edition of] 1984, they realised that that was here to stay. But they saw the decline of the King James or Authorised Version, and other such things. A number of things just came together, really. And also, they wanted to get a truthful idea of what Bibles people were actually reading and studying from. What the serious student [was using]. Now, we defined “the serious student” [in this project] as not being a university, college or seminary student …

Alex jr: … who’s doing it because he has to, to get a [clerical] collar round his neck …

Alex sr: … nor the guy who just occasionally reads his Bible, nor—and we don’t want to be unfair here—the guy who simply says, “I like my Bible because I get daily inspiration from it.” We’re not pooh-poohing that, by any means, but [we mean] the guy who says—and, of course, I include the ladies by ‘guy’—“I want to study my Bible seriously.”

Alex jr: In many Protestant countries—and Catholic and Eastern Orthodox, actually—you had the idea of the Pietist or devotional reader, who reads a small extract of the Bible [at a time]. You also have the agnostic and atheist appreciator of the literary foundational quality of the Bible.

Alex sr: Yes.

Alex jr: But you’re talking about something which has died the death in many parts of the world, but which when you were growing up in Scotland was extremely strong, and has been very strong in parts of the American South, where I think your guys are from, which is a stereotype but a true one: a backwoodsman, or, in your case, a disadvantaged boy …

Alex sr: In British terms, a working-class man who’s not an idiot; who actually can read, and does read.

Alex jr: One of the best books you gave me recently, by the way, is The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes (Jonathan Rose): an absolute gem focusing on the English industrial towns. But particularly in the Scottish and North American context, you’ve got these people who are extremely literate by the time they’re in their early teens, and if they’re disenchanted with church, state or anything around them—shallow family life, shallow entertainment—they will withdraw and read their Bible seriously. That’s the kind of people you’re talking about.

Alex sr: One of the things that quite shocked me into some sort of reality was the realisation—I can’t remember when it first came, but there’s an interesting confirmation of it somewhere—that in places like Tennessee and Kentucky, where it’s imagined that the people are stupid, there were very learned students in these areas. And the Bible colleges were quite good colleges [there].

And, strangely enough, I remember getting a confirmation of it from The Waltons [TV historical drama of an Appalachian family in the Depression era]. There were hints there.

We’ve got a very distorted view of our own [English-speaking] cultures now. The seeds have been sown now; a lot of rubbish.

Alex jr: You’re now starting to flick through your Serious Student Project folder.

Alex sr: Basically, a lot of things came together, and this has been the result of at least ten years’ [work]. But getting historical information can be very difficult, and some of it is inference, and some of it is that you get information here and information there, and you’ve got to draw the best-fit line on the graph.

Alex jr: Lots of extrapolation.

Alex sr: Extrapolations, but that’s all it can be.

Alex jr: You have little data points, from about the Reformation onwards, which allow you to extrapolate what percentage of the population in the United Kingdom and the United States, in particular, were serious readers. And in the early centuries, so until about 1800, the Bible was basically all that was in your shack, wasn’t it?

Alex sr: That’s correct. And basically, dear American friends, you will be pleased to know that historically, the Americas have always been a few percentage points ahead of Britain, largely because the people who went to America were Bible readers.

Alex jr: This has been an open secret in the English-speaking publishing world for a long time: that the Canadian and US branches of British publishers would basically increase the quality, or retain the quality of a book for longer, when it was hollowed out and popularised for the London market. And American and Canadian readers have long been known for having fewer books—but that they actually digest.

Alex sr: And, again, this came through in The Waltons: that people like Thoreau are read longer in the Americas than we read our Dickens or our [other nineteenth-century authors from] here.

Alex jr: I know it’s pompous and pretentious now, but you see it in the New York journalistic tradition: the long-form article, the self-regarding novel, the Great American Novel.

Alex sr: The long essay has died out in Britain, largely, but you do get it in American newspapers sometimes.

I’ll just summarise some of the pages for you. Basically, we’ve got to understand that from the earliest times, Christians have been a literate people. We’ve encouraged literacy, especially Bible literacy, because right from New Testament times—if you’ve got people coming to a New Testament house, where the church is in New Testament times—they’re not there for an hour. They’re there for half a day or a day. They’re there for quite long periods. And we know this from people like Justin Martyr.

Alex jr: Of course, because they were walking in from the countryside.

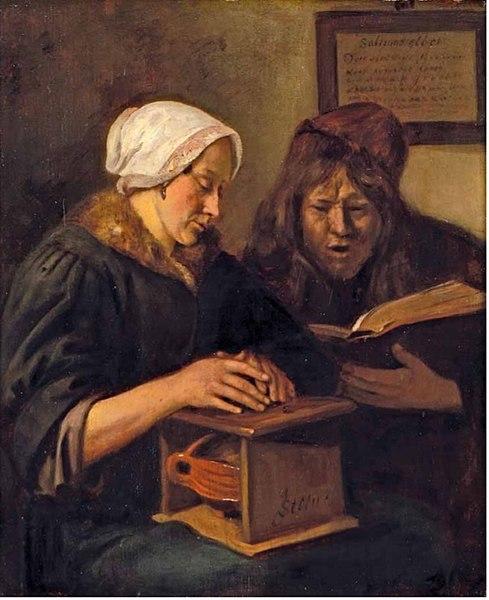

Alex sr: They were walking in from distances, they were staying some time, having a meal, and they would minister to each other, and they would help each other to read. Now, initially, of course, it was Bible oracy, i.e., ‘oral’ + ‘-cy’.

Alex jr: Oracy, which is the ability to understand accurately and grammatically what’s being spoken to you, at a high level.

Alex sr: And in a culture where you are listening and memorising. Later on, there’s a very good example: when Jerome [alias Hieronymus] revised the Latin Old Testament into what we call the Vulgate, which means ‘the Common Version’, he changed the word in Jonah [chapter 4] that we translate as ‘gourd’: from the Latin hedera, which means ‘ivy’, to cucurbita, which means ‘a gourd’.

[Jerome’s revised word] was a bit more accurate [to the original Hebrew noun qîqāyôn]. But Augustine’s congregation went nuts. Bananas. They wouldn’t have this. There was an uproar.

Alex jr: And the reason you’re telling us this is because [it illustrates that] by the fourth century, the Roman Empire in the West was a shadow of its former self—there was very little military and political power left—but the strength, the backbone of the Latin-speaking world was the well-educated church …

Alex sr: People treasured what they held dear, and they memorised their Bibles, and they concentrated. They didn’t have television or other things to distract them. And also, [they were well-educated] because if you got a letter from [the Apostle] Paul, the letter was read and re-read in the churches. You didn’t have [an attitude of], “Let’s look at Chapter 1, the first six verses.” It’s, “Let’s read the letter.” So you put an hour or two aside to read it.

So, basically, that’s how [literacy in the church] started. And then it never died down. Remember that we’ve got—in the Middle Ages, when the so-called Dark Ages come—the monasteries, whatever we think of their faults, which preserved learning both by gathering manuscripts and by producing manuscripts and treasuring them and storing them, and also going to the villages in Britain, and probably in other countries, and looking out for a boy—usually a boy, occasionally a girl—who had some intelligence.

And they would say to the parents, “If you surrender your lad to us, we will look after him and give him an education. He’ll become a monk, and he’ll write the Scriptures; he’ll work in our scriptorium.” And so they kept learning alive, and especially in the Celtic lands, in Ireland and places in the west.

Alex jr: There’s a famous book of not very long ago by Thomas Cahill called How the Irish Saved Civilization, that goes into this.

Alex sr: Yes. And so these Godforsaken places out of the way, the extremities of the West, actually were important.

Alex jr: Because Rome didn’t have a stranglehold [there].

Alex sr: Rome didn’t have a stranglehold. And then, of course, came the Renaissance and Reformation, and then we got a very marked increase in literacy. And let’s be honest: the men of the Renaissance and Reformation, men like Erasmus (and there were others), had a real concern that the common man should have access to the Scriptures.

Alex jr: Tyndale put it best, didn’t he? “The boy that driveth the plough” must be able to read the Bible better than a priest of his own day.

Alex sr: So that’s how it started: the repeated hearing and memorisation of the Bible is itself a form of literacy. We call it ‘oracy’ now.

Alex jr: You see this not just in Tyndale but in another man of his generation, Thomas Cromwell, who in the King’s name—Henry VIII—causes an English Bible to be chained to the pulpit in every parish.

Alex sr: We’ll come to that later. Very clever [of Cromwell].

Alex jr: I’ll highlight that already, because it means a group of keen readers can gather round and go through a Bible book in that way.

Alex sr: Absolutely.

Alex jr: And, of course, when you get to the King James Bible [1611], on the flyleaf, often misunderstood, we read in italics: Appointed to be read in churches—which doesn’t mean ‘licensed’, as it does in Late Modern English. Early Modern English ‘appointed’ means ‘so conceived or made fit’—[in this instance,] that it will have good rhythms and cadences to be read aloud.

Alex sr: Yes, [as with Jonah 2 in the KJV:] “He appointed a fish”, meaning ‘prepared it’.

Alex jr: [So the KJV was] drafted that way.

Alex sr: And with Bible oracy, the idea begins to develop in the common [not élite] mind that “This Bible that I’m listening to, I would like actually to read the pages.”

And so you start, in a few cases, to look at a Bible, chained in a church or in a monastery, it’s shown to you, and they’d maybe read to you some of Jonah, and you’d say, “I know this story,” and then the monk, or whoever, would point out the words to you.

And that’s one of the ways they spotted intelligent people: [if] you could actually follow the lettering.

Alex jr: This is probably one of the reasons why the native Celtic mythology, particularly the short gems, were written down in the vernacular by the Irish and Welsh monks, and later by the English churchmen: so that these bright lads who’d heard this at their mother’s knee would be able to read along with it, so that they would then be able to write good Latin later.

Alex sr: Yes. Now, in Scotland—and I’ll speak obviously, as a Scot, a lot about Scotland—from 1579, every householder who could afford a copy of the Bible had to have one. It was the inexpensive Geneva Bible. It was inexpensive.

Parish schools were set up from 1616, and Sunday schools from 1780. And they taught the Bible and catechism [basic instruction in articles of faith].

And in addition to that, there were three people [of significance] in a Scottish parish: the local laird (‘laird’ is the Scottish form of ‘lord’), the minister (the priest), and the schoolmaster, known as the dominie. These three, together or separately, looked out for lads—and other Scots of means [did], as well—and occasionally lasses, who had something about them.

Alex jr: And you can attest that as late as the 1950s, a disadvantaged bright boy like you was spotted in Central Scotland—in your case, by all three: the local laird, the local schoolmaster or dominie, and the local minister all took you under their wing.

Alex sr: Yes.

Alex jr: So they probably had secret confabs, didn’t they?

Alex sr: Oh yes, they met regularly. That’s how a Scottish village or parish was administered: the three-pronged [approach]. And, for example, a constable—including in England, I think—didn’t act on the authority of the central government; he acted on the authority of the parish. That’s the origin of a constable.

Alex jr: He took his oath seriously.

Alex sr: Now, this lad was known as a lad o’ pairts (‘lad of parts’), and that’s a well-known Scottish institution, if you want.

Alex jr: And, of course, the meaning of ‘parts’ there (more generally, you hear of ‘a man of many parts’) is ‘accomplishments’ or ‘skills’.

Alex sr: Partes in Latin, because Scots is influenced, obviously, by Latin learning.

In England [and Wales], the SPCK, the Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge—[jocularly:] it later became ‘for the Prevention’ and then ‘for the Perversion of Christian Knowledge’, but never mind!—soon after its foundation in 1698, set up schools for the children of the poor [teaching literacy through the Bible in both English and Welsh].

Now, remember 1579 in Scotland, because that’s Knox. Knox wanted to ensure that everybody read. Knox was a great man. He wasn’t a very nice man sometimes, but he was a very great man. He made sure people had a Bible and schools, and the institutions there.

In England, [the key date] was 1698—ten years after the Glorious Revolution—which was when [the SPCK] set up schools for the children of the poor. It was a woman, Hannah Ball, in 1769, who set up what is generally regarded as the first Sunday school, and then in 1780, Robert Raikes set up Sunday schools to teach both adults and children.

Alex jr: There was also the gentleman of German origin, George Müller, in Bristol.

Alex sr: Yes. These all taught literacy through the medium of the Bible and catechism. By 1831, it’s reckoned that Sunday schools were teaching over one quarter of the population!

Alex jr: So in 1831, before Queen Victoria accedes to the throne, essentially the church is teaching the young people. And with the [political] upheavals of Early Modern times not far behind them, one of their concerns was that “if we don’t do this, people will be told a pack of lies about their own history.”

Alex sr: And remember also that in 1832, we have what’s called the Great Reform Act, with the expansion of voting in England. So these things are all gelling together, as it were.

Alex jr: Yes, and again America takes the lead, because the early American Republic was very express about this, certainly on the east coast: that in order to live in a free republic, you had a duty as a citizen to read long news articles and work out where you were being tricked, and vote accordingly.

Alex sr: Yes, that’s right. And then, from 1698 up to 1831, you get [the foundation of] a whole series of Bible societies: the SPCK, the Scottish SPCK, the Naval and Military Bible Society, the Religious Tracts Society, the British and Foreign Bible Society, the National Bible Society of Ireland (1806), the Bible Society of Northern Ireland (1807)—notice even then the Irish division.

And then: 1809—the Scottish Bible Society; 1816—the American Bible Society; 1831—the breakaway [from the BFBS] Trinitarian Bible Society.

Alex jr: So you’ve got a dozen there!

Alex sr: You’ve got a dozen there. Now, these are giving away cheap, subsidised and free Bibles. Plain Bibles, sometimes. I had one, for example, that the Americans have now got [from me], that actually had stamped on the cover, “Sold under cost, 10d.” [ten pence, or less than a shilling]. That was a British one.

Alex jr: So they’re allowing you to know here that—far from it being the state coffers propagandising people—these are local boys made good, in many cases, who wish their own area to have the Bible.

Alex sr: Early Gideons.

Alex jr: Not to push a denominational agenda, but for the sake of literacy.

Alex sr: That’s one of the reasons why Bible societies were set up: to stop there being a denominational bias, that people could co-operate [from various churches]. And it’s a good way: Christians with different views can, just as you contribute to a medical disaster or earthquake disaster [relief fund], you can contribute to a Bible shortage [relief fund]. You’ve got different views, but all Christians of goodwill can contribute to a central pot for people to get Bibles.

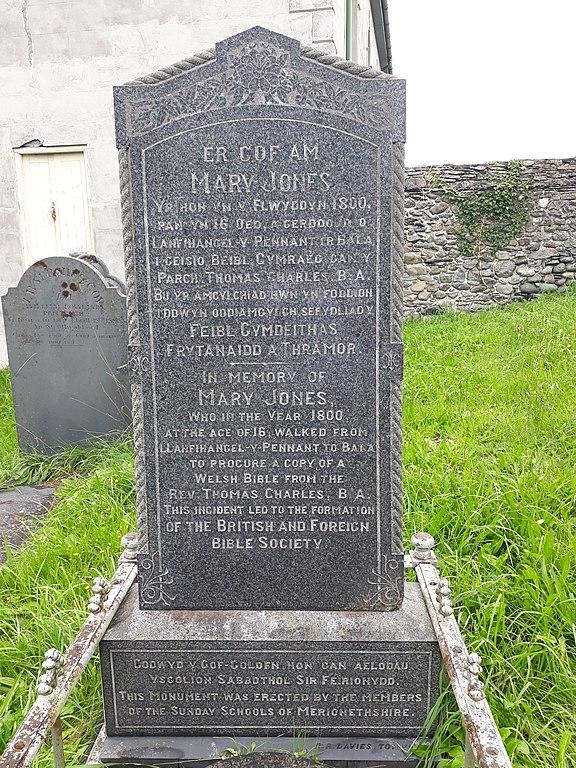

Alex jr: This is very much what happened in North Wales, with the setting-up of the British and Foreign Bible Society, because London ministers heard the pitiful story of Mary Jones [having to walk a whole day to get] her Bible in [what’s now] Gwynedd, and realised, “We’re going to have to get all of the churches on board to stop this problem.” Because, of course, Welsh Bibles could never be printed at cost; they were always going to be extortionately expensive, so you needed to subsidise them.

Alex sr: So the point is, it was the desire to know and read the Bible that really drove up literacy rates, both in the UK and also in the US.

Alex jr: Why did the population, for several hundred years, in the English-speaking world and the Celtic countries, want to read the Bible? There’s a significant number of our viewers who post occasional comments [under UK Column News uploads] like, “King James put his Bible into circulation in order to inject Gnosticism, or to chop away certain books which were part of the Bible before the Reformation.”

Alex sr: No. That will become very clear very shortly. No, no, no. James [VI of Scotland and I of England], for all his faults, was “the wisest fool in Christendom”, as they called him. James genuinely wanted people to have the Bible. And we’ll come to it—you’ll see: even the recognition that there was a Geneva Bible before the Authorised Version was adequately taken account of by the Crown. They didn’t ban it.

The Crown and its ministers played things very coolly and very rationally, against a despotic king. Henry [VIII] was [himself] better informed against the worst [side of] Henry; there were two Henries, if you want. Henry in his better moments allowed his ministers to get away with things that were for our benefit.

Alex jr: So not long after Tyndale had been burned by [Holy Roman Emperor] Charles V’s agents in Brussels, King Henry VIII pretty much knew that the same [English government] ministers who’d ordered that were allowing Tyndale’s Bible to be disseminated.

Alex sr: Yes. I think there was a realisation by Henry and by others that reform was inevitable; that there was an underswell.

Alex jr: England in particular, at a political level, was completely fed up with Roman domination by then [the 1530s].

Alex sr: Yes. Éamon Duffy and others say that the [English] Reformation was top-driven. There’s some truth to that. The forms of the Reformation were top-driven, but the desire for reformation was really in the population. The population was fed up with exploitation by clerics and by the Roman power.

Alex jr: I do know that from about the 1970s and 1980s onwards, so the generation of historians who were in vogue when I went up to senior school in the 1990s, they have a certain smarm about them, the English [historians] in particular: “Let’s be honest here, chaps; the Reformation happened because of palace intrigue and sexual affairs and what not.”

And they’re not doing this as Vatican propaganda; it’s because they have a blind spot in their understanding of the world, which would be the spot that you’ve just referred to, which is that there were gentry—particularly in England, I think—who had got a bit more money and time than in previous generations, and they were not happy with the status quo any more.

Alex sr: When Tyndale graduated and he went and got his job as a tutor in Gloucestershire, and he was out for a walk one day, apparently, he met a parish priest somewhere, and he said, “Do you know who the Beast of Revelation is?” And the poor parish priest pulled him in, shut the door, and said, “Don’t you know that’s the man of Rome?” That was not uncommon in England.

People lampooned the clergy; they didn’t trust many of them. They realised there were good clergy around. If you read Chaucer, the decent Parson [in the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales]:

Christ’s gospel truly would preach …

This noble ensample to his sheep he gave:

that first he wrought, and afterward he taught.

Chaucer, Prologue to the Canterbury Tales

[That is, he practised what he preached.] But a lot of them were barely literate.

Alex jr: Yes, and they were there to have their way with village girls, basically.

Alex sr: Anyway, in 1526, Tyndale—using Luther’s Greek New Testament from Erasmus—issues his New Testament in English. It’s produced in Antwerp; it’s banned here.

Alex jr: It was smuggled into Britain by German dockers.

Alex sr: And the first edition, remember, was sold to the Bishop of London, [Tunstall,] who ordered it to be bought up [upon importation to England]. He paid money for [every copy in the print run] and destroyed them. And Tyndale said, “Good! I needed money to do my second edition, to improve it!”

Alex jr: This has been a long British Establishment tradition, hasn’t it: buy up the entire print run of a naughty book or magazine.

Alex sr: So at that point, I think it’s pretty well established that, if you want, literacy—reading literacy, I’ll put it that way—was about four per cent of the population.

Alex jr: But if it’s spread evenly, that means that everyone—and the philosophers of that age, like Hobbes, talk about this—has, on his street or in his village, a chap whom he knows as [well-educated].

Alex sr: That’s what I’m coming to; you have to add a “Bible-oral addition” [to the general literacy rate], because if you have a Bible, and you can read it, you’ll find, of an evening or a weekend, two, three, four, six of us at your door, and you will read to us.

Alex jr: Maybe you’ll be paid in kind: you might get a kipper for it, or something.

Alex sr: And if you’ve got a sympathetic vicar or minister, you’ll find that you can gather at the parish church, and the Bible is read. It’s not illegal [in the 1530s].

Alex jr: You might find people discussing their political and economic woes as a result of being in that setting and being literate.

Alex sr: And therefore, you pretty well have got to add a big chunk [to the literacy rate]. Now, I reckon about twelve per cent Bible literacy-oracy. So I reckon that in Tyndale’s day, the nominal four per cent who could actually read-read has got to be multiplied to about sixteen per cent of people who had an active command of the Bible.

Alex jr: Of course, as soon as you’ve got movable type coming in [as a widely-used technology], just in this generation, you’re no longer having to deal with black-letter or manuscript hand. Nice, clear, modern type, now known as Book Antiqua, makes it possible for children to pick up reading very quickly.

Alex sr: That’s an interesting point, because when the Geneva Bible was produced, it was produced in clear Roman type. When the first edition of the Authorised Version came out, it was back to Gothic!

Alex jr: For the sake of looking beautiful and ornate.

Alex sr: But it soon was abandoned for Roman type, because people realised that they wanted a Bible they could actually read.

So then comes Miles Coverdale. What happens there is, [the English New Testament by] Tyndale is banned in England: Henry will have none of it. However, Thomas Cromwell, England’s greatest, best civil servant …

Alex jr: … the de-facto prime minister …

Alex sr: … really decides that he will use Tyndale’s work and encourage it. So basically, Coverdale produces his whole Bible.

Alex jr: It’s [Coverdale’s] psalter which is sung in the Anglican Church and by the Episcopalians worldwide, so people will know his version of the Psalms.

Alex sr: Yes. I come to this a bit later, as well. I won’t go through all the figures, but the important ones are: in 1526, there’s a reading literacy of 4%, an oral addition of 12%, making 16%. The Geneva Bible comes out, between 1539 and 1644 [in about 150 editions].

This [next figure] is basically a result of the Geneva Bible, because the Authorised Version hadn’t come out yet: in 1611, the literacy rate in England had gone up tenfold to 42%!

Alex jr: So before the King James Bible comes out, there has been a tenfold increase in people who are actively able to read?

Alex sr: The Geneva Bible was largely responsible. It was enormously popular.

Alex jr: We can’t despiritualise [the Geneva Bible translators]—they were Puritans—but one level of what they were doing was, they were English dissidents: dissidents who went off to Geneva, where it was all at—the freedom, the money and the technology was there—and they sent back into England a product that was able to increase tenfold the amount of literacy in the country.

Alex sr: And another 29% [had] oral [literacy]. So there was a 71% Christian literacy rate at that point [1611]. Very high!

Alex jr: So [in the year when the King James Bible was first published], it was already unusual, verging on exceptional, not to be able to read well yourself—and almost unheard-of not to have anyone in your circles who could read.

Alex sr: Good Bible knowledge was widespread, put it that way.

Alex jr: So we can lay to rest—I know people have a variety of reasons for saying this, and are repeating what they’ve heard—this idea that the King James Bible was some élite political trick?

Alex sr: Absolutely, absolutely.

Alex jr: And it didn’t do anything on its own, did it? It’s part of a tradition [of English Bible translation stretching back eighty years] that you’ve just outlined. A groundswell from the people.

Alex sr: Yes. And then, in 1837, when Victoria becomes Queen—and now as a result of the Authorised Version—you’re talking about two-thirds, 67% of the population, being literate; 22% [had oral literacy]. Now that would decline because as the actual literacy [rate] goes up, the oral literacy [rate] obviously comes down, because more people can actually read-read.

Alex jr: What else is happening from the late eighteenth century onwards—particularly in Scotland in the first wave, but then later on in England as well, and certainly in Wales—is that free churches become a major phenomenon, for a mixture of spiritual, political and economic reasons.

People [at this stage in British history] say, “We’ve had it with the Church of England or the Church of Scotland; we can do it ourselves; our own guys are perfectly capable of preaching from the Bible; and while we’re at it, we’ll set up a local bank (or, more accurately, a building society); we’ll educate our own children; and we have very little need of central government.”

Alex sr: There’s a very good illustration of this, a bit later [in date], in Thomas Hardy’s Jude the Obscure. Remember, it’s [set in] a time when to get into Oxford or Cambridge, you have to be a member of the Church of England, an Anglican; you cannot get in as a dissident, Nonconformist, student. That [requirement] was a bit of a blip [in the level of liberty] at that point.

And Jude cannot get in, but the truth is that Jude is actually more learned than many of the students there. There’s a scene where he corrects some of the students on the Creed, for example.

Alex jr: He quotes the Creed in Greek [in the film adaptation, in Latin]. But this was true. I mean, Oxford was an intellectually lazy environment then in many ways compared with St Andrews, where you were at, but it’s a universal truth, I think, of this time—and, again, even more pronounced in America and in the Commonwealth Dominions—that free churches, or low Anglican churches that did things all locally, had a lay-member standard of knowledge that was better than the minister or clergyman in the Establishment setting.

Alex sr: Yes, and that is still largely the case, if I can digress to the present. The present bishops of the Church of England know full well that there is a shortage of clergymen, but they will not do the obvious thing, which is to empower and even ordain unpaid ministers to be priests.

Alex jr: They have, in the Church of England Canon Law, [Articles] E7 and E8, which go into detail about the licensing of lay readers to take services.

Alex sr: Which they will not operate.

Alex jr: And they deliberately don’t do it. We’re sitting here in the Diocese of St Albans, where the Bishop has been quite express about this: “I will not do it.” Now, this year, we’ve finally discovered at least part of why. It’s because they basically want to dispense with the clergy, and for that you need a created and artificial shortage.

Alex sr: And he knows full well that there are men, so-called laypeople, in his church who are better educated than many of his priests.

Alex jr: So you’d show them up, basically.

Alex sr: They know it, but they won’t release the power of that [ability to ordain selectively].

Alex jr: They’re now pretending that the clergy are the obstacle [to church growth], because in the old model, they get appointed for life, and they’re being caricatured as sticklers for the old ways. So the C of E ascendancy now basically wants—for a post-literate society, if we retain this theme of literacy—a touchy-feely, post-literate kind of service.

Alex sr: What it’s trying to do is to destroy/control the Church of England before the power of educated Christian Bible-believing literacy asserts itself.

Alex jr: So this [generation] is their sweet spot for action: if they leave it too long, the dissidents will have overtaken them in many ways.

Alex sr: If the dissidents remain, they’ll take over.

Forthcoming instalments of the Literacy podcast:

Part 2: Who doesn't want us to be able to read

Part 3: How we can teach ourselves to read again