They will come for you eventually

As Prokofiev fans will testify, not all warnings are equal. Paying heed to a government warning, for example, is likely to land you in the soup and it is, therefore, notable that there were no state-issued warnings about the Online Safety Act (OSA) 2023. Quite the reverse, of course: ministers insisted that we would all, somehow, be ‘safer’ as a result of it. This was a lie then, and it is most certainly a lie now.

The dustbin lids of the independent media sounded a terrible cacophony in the run-up to royal assent; UK Column documents the entire timeline in its Censored section. Some of the events of the past few weeks have shown exactly what the din was about, parts of which I put into a Telegram post recently.

Cheshire Police announced recently that they had arrested a woman for offences under s19 of the Public Order Act 1986 and s179 of OSA 2023. They then tweeted that:

It’s a stark reminder of the dangers of posting information on social media platforms without checking the accuracy. It also acts as a warning that we are all accountable for our actions, whether that be online or in person.

This appears to have been in relation to the widespread speculation about the name and religion of the suspect in the Southport stabbings.

It is important to point out that the woman is alleged to have made comments about the speculation, rather than to have taken a guess herself. In fact, this is completely critical, and OSA 2023 does not contain any provision to prohibit such reporting. Nonetheless, police appear to be labelling her as someone that has wilfully dressed something up as ‘fact’ or ‘news’, "without checking the accuracy". Section 179 OSA 2023 says a person commits an offence if a message sent "conveys information that the person knows to be false" and that "the person intended the message, or the information in it, to cause non-trivial psychological or physical harm to a likely audience". The Act widens the goalposts by adding that "it is not necessary for the purposes of subsection (1)(c) that the person intended to cause harm to any one of them in particular (or to all of them)", so we are immediately into the zone of imagined harm, rather than actual or intended harm; a specialist area for police in the 2020s.

Legislation is pretty dull, but every so often you come across a piece that blows your socks off. Section 180 OSA 2023 is one such. It states that "A recognised news publisher cannot commit an offence under section 179." I put that in bold, but I feel the Government should do, too. You really did read that correctly. The BBC (a “recognised news publisher”), for example, may send a message they know to be false, with the specific intent to cause "non-trivial psychological harm". In other words, state-sponsored propaganda is legitimised in statute by OSA 2023.

If you suspect that the Government would not enter into the business of intimidation, I will remind you of the minutes of a Sage meeting in March 2020, in which techniques for elevating the “level of personal threat” were planned.

Not an accident

It may surprise you to learn that the Government is a terrorist organisation, something which is made very clear by the Terrorism Act 2000. Section 1 explains that terrorism is “the use or threat of action where—the use or threat is designed…to intimidate the public or a section of the public, and the use or threat is made for the purpose of advancing a political, religious, or ideological cause.”

This is not news to the United Nations, which states—correctly—that the very origins of terrorism are to be found in government.

The challenges of countering terrorism are not new, and indeed have a long history. The term“terrorism” was initially coined to describe the Reign of Terror, the period of the French Revolution from 5 September 1793 to 27 July 1794, during which the Revolutionary Government directed violence and harsh measures against citizens suspected of being enemies of the Revolution.

— Introduction to International Terrorism, UNODC, 2018

One-world terror

With regard to policing and the transmission of information, which subsequently turns out to be false, it cannot automatically be presumed to be loaded with the intent to either stir up racial hatred, or to cause psychological or physical harm. However, there is increasing precedent in this area, seen most obviously in the case of Sam Melia, where the Crown Prosecution Service gave a description of the magnitude of his intent, based on very peripheral and circumstantial evidence. Sending messages which turn out to be inaccurate, or even reporting on speculation, may be considered reckless, but recklessness is not one of the elements which may make up an offence under s179 OSA 2023.

Rules for thee

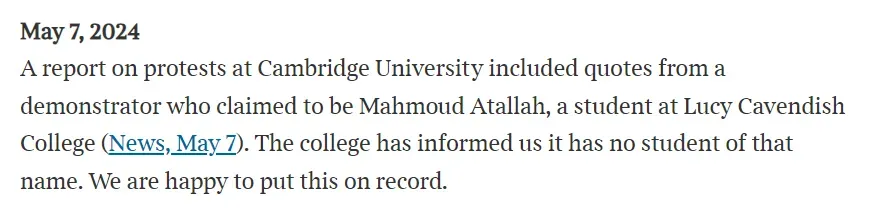

What is, surely, reckless, is to ignore the warnings of Pastor Niemöller, he of “First They Came” fame. Since the Cheshire arrest, the degree to which “recognised news providers” may act with impunity has been exhibited in the multiple attacks on David Clews, of Unity News Network. The Sunday Times, the Guardian and the Daily Record have ripped into Clews. In his own words, he’s a big boy, and he can take care of himself; but that is not the point. The point is that these newspapers have made references to his wife and child and embellished their pieces with strong inferences that both Clews and his wife have been involved in prior criminal activity. This is simply not true.

However, I refer you to s180 OSA 2023, which almost encourages this sort of attack. These pieces are most certainly intended to cause non-trivial psychological harm. I would say that they committed to print information which they knew to be false, but the rank quality of these publications and their employees colours this grey. David Clews has subsequently spoken to Sonia Poulton, a conversation worth listening to (from 28 minutes).

This is not a story about inaccuracy, or falsehood; it is about the priming of the British public, over decades, to accept that surrendering freedoms in the face of the confected spectre of “radical Islam” is a fair trade. What, one wonders, would have happened if messages had been sent, suggesting that the suspect in the Southport killings had been white British, with white British parents?