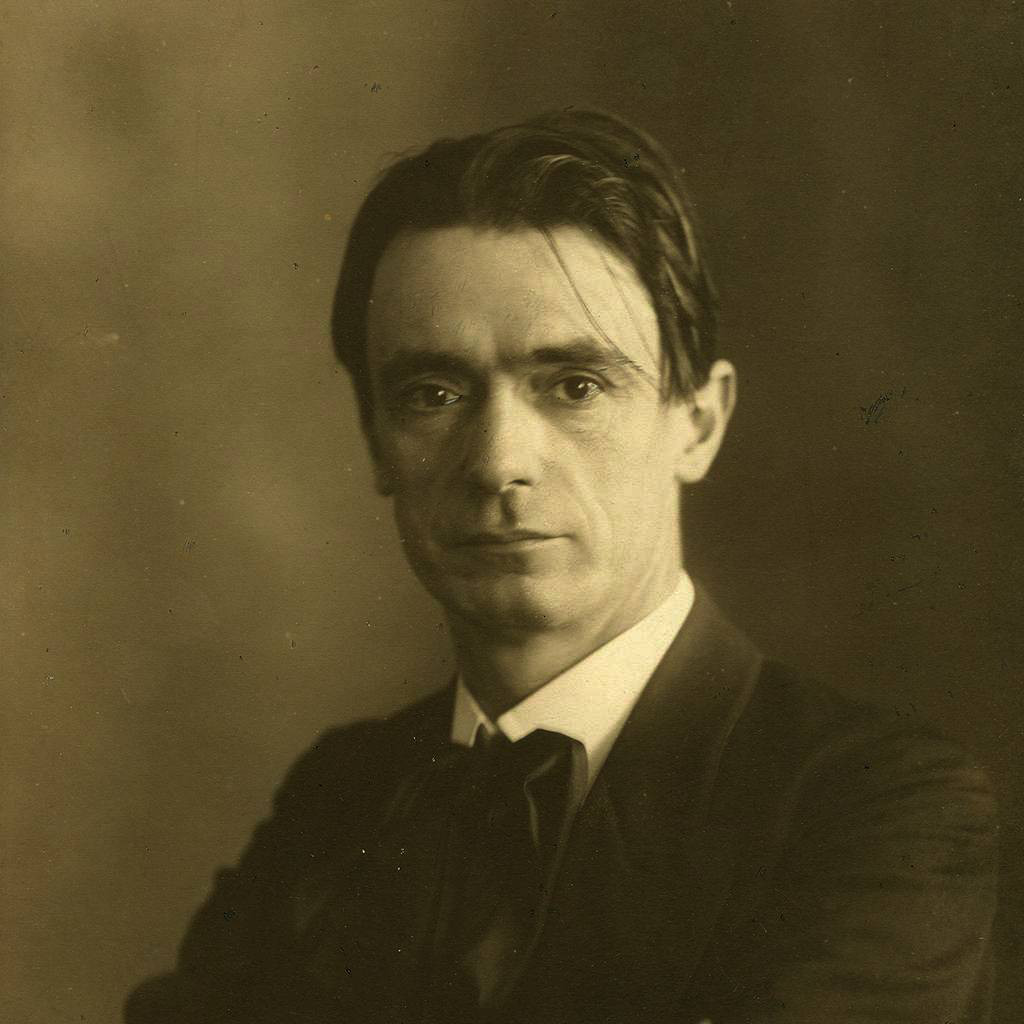

Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925) was an unconventional Austrian philosopher, spiritual explorer, educationalist and environmentalist. Centres, groups, schools and other associations descending from his work are now widespread throughout the United Kingdom, Europe and North America, with further centres scattered through numerous other countries, including Egypt and parts of sub-Saharan Africa. In the UK, Camphill, developed during and after the Second World War (and now with branches in many overseas countries)—which specialises in the curative education and lifelong care of mentally disadvantaged youngsters and adults—and the Steiner-based Waldorf Schools Fellowship, which describes itself on its website as “the largest group of independent non-denominational private schools in the world”, are the largest such groupings.

Steiner-connected enterprises are to be found in such various areas as agriculture, horticulture (including vineyards); education and special education; medicine; therapeutic dance known as “eurythmy”; the visual arts; and a religious sect called The Christian Community. Behind all these ventures is a view of history and of man which Steiner termed “Anthroposophy”, meaning “wisdom of man”, leading into what he termed “spiritual science”. His term “Anthroposophy” was developed in conscious contradistinction to the “Theosophy” (meaning “wisdom of God”) associated with Madame Blavatsky, with whom Steiner had fallen out. (For categorisation, both can be seen as developments within, or from, the broad tradition known as Rosicrucianism. However, that does not mean that either or both of these late-nineteenth-century currents is broadly accepted, or accepted without adverse criticism, within the Rosicrucian tradition).

Anthroposophy on its own is a broad field; and my own knowledge, though fairly extensive as regards core Steiner literature, study groups and some practical experience, is limited to the United Kingdom. In addition, my reading of numerous factually-based critical articles suggests to me that Anthroposophy in the United States is experiencing parallel problems. From that ambit, I offer a few pointers which I hope will assist interested readers to do some further research for themselves, beyond the propaganda of the devotees of the Steiner movement. The readers I am thinking of might typically have come across Steiner-related ventures and might be uncertain as to how to evaluate them, whether as individual ventures or in the context of such a broad movement.

Fifth Gospel

Firstly, then, I invite interested readers to look up a core—in the sense of being much revered by all Steiner affiliates—text, readily available on the internet from the Rudolf Steiner Archive, namely The Fifth Gospel. This is the title of a series of five lectures delivered by Rudolf Steiner in Oslo in October 1913. The dense and driven style might seem hyper-conceptual and impenetrable to some, but perseverance pays dividends. To ease demands on a reader’s time and patience, let us focus on Lecture 2, in which Steiner purports to examine the developing state of consciousness of some of Christ’s’ disciples in the period leading from the death of Jesus up to Pentecost.

Steiner asserts a “clairvoyant observation” which gives him special insight into what was going on. He writes:

That earthquake shook the tomb in which Jesus’ body lay, and the stone which had been placed before the tomb was ripped away and a crevice opened in the ground and the body fell onto the crevice. Further vibrations caused the ground to close over the crevice. And when the people came in the morning the tomb was empty, for the earth had received Jesus’ body; the stone, however, remained apart from the tomb.

This assertion asserts new knowledge, not known to the historical record nor to archaeology. Any critical evaluation requires us to ask the question: How does Steiner know that Jesus’ body fell into a crevice? As he called his approach “anthroposophy” (literally meaning “wisdom of man”) and propagated the concept of “spiritual science”, it seems reasonable to ask: What evidence does Steiner adduce? This critical approach is further justified by the notion of “the resurrection of intellect” which permeates the vast Steiner corpus like the lettering through a stick of Brighton rock.

In Steiner’s case, the type of intellect in question is a development of the Aristotelian. Steiner regarded himself as a reincarnation of Aristotle, though with some other interesting incarnations in between, including Thomas Aquinas. (See Rudolf Steiner’s Mission and Ita Wegman by Margaret and Erich Kirchner Bockholt, Rudolf Steiner Press (1977), p. 61). Whether Steiner was factually correct in this insight is, of course, highly debatable, but that is a side-issue here.

The point is that Steiner’s ‘Anthroposophy’ attempts to apply a further development of Aristotle’s thought to various issues and problems of our time. Just what this further development might be is not clear; and despite various conversations, lectures and reading through the years, I have been unable to discover it clearly—apart from one unvarying fundamental. The starting point when addressing any topic in an anthroposophical milieu—for instance, a study group—is invariably some ‘indication’ or ‘idea’ left by Steiner.

For instance, if the topic is ‘national sovereignty’, then the permissible stance in a Steiner study group is to view it as a philosophical viewpoint which may or may not have been useful once, but which is now out of date. This is, of course, a perfectly reasonable philosophical standpoint, but it is not acceptable in an anthroposophical study group for anyone to disagree with what is felt to be Steiner’s indication— always the starting point for anthroposophical enquiry— in order to promote another view.

Even a nuanced tangential difference from the view of ‘the Master’ is not tolerated, in my experience. “When I have Steiner’s spiritual development, then I might feel able to challenge him” is the implicit notion which supports this imputed inerrancy. Using Steiner’s ideas and indications as starting point and guiding framework, sense-free thinking, also referred to as supersensible thinking, then relates these to the external world, and ‘sees’ and interprets the facts in line with Steiner’s indications.

Anyone who has encountered some of the tighter edges of the type of thinking designated as Thomism within the Catholic Church might have some idea of the type of thinking involved, though Aquinas himself acknowledged the limitations of thinking. By contrast, the contemplative tradition in the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches is on another trajectory. ‘Negative theology’ (apophasis) is unknown or alien to the Steiner movement, where all thought and activity is conducted within the indications and framework set by the Master.

The tight following of Steiner’s indications spells freedom to some but dogmatic confinement to others, and it periodically produces frictions which test the movement. A major schism occurred before the Second World War among European Steiner centres: see, for example, an account in The Occult Establishment by historian James Webb (1986), a somewhat neglected classic which is both thoroughly researched and readable and deserves to be better known. ‘Split’ might be a trifle excessive a noun to describe the present situation, because the more independent-minded tend to leave the Steiner movement, or to maintain only partial linkage.

To cut to the quick—this being an essay, not a book—at the end of Lecture 2 in his Fifth Gospel series, Steiner gives the source for his arresting new information that Jesus’ body was received into a crevice in the earth. He, Rudolf Steiner, is reading from the ‘Script of the World’ , alias the ‘Akashic record’. In essence, this term refers to the hypothesis that a record of “everything that has ever been thought exists” on an inner plane of perception. The quotation is from Teal Swan (not herself an Anthroposophist), whose talk on the Akashic record is available online.

That inner plane, so the idea goes, can occasionally be accessed by those with appropriate psycho-spiritual development. Steiner, in one of his core books, An Outline of Occult Science, 2011 translation (published in a previous translation as An Outline of Esoteric Science, 1997), has a chapter in which he describes developing ages of the earth going back ages before Man first appears in the fossil record. This seems to imply that Steiner felt he could access the so-called ‘record’ from eras before Man left memory traces, stored within the “collective unconscious”. According to Steiner’s vision/concept/illusion (take your pick), earlier versions of Man pre-existed in some protean sense in a kind of spiritual mist (my paraphrase), long prior to Man as we know him (or her) from the fossil record—a species which, on latest findings, extends back only some 195,000 years. Anyone who seriously wants to get to grips with Steinerology should obtain this book and read this incredible chapter; but without expectation of historical or scientific evidence, as it will be found wanting.

Higher Worlds

In his book Knowledge of the Higher Worlds, translated by Osmond/Davy (2004), Steiner gives a series of mental exercises, sometimes referred to as ‘meditations’, in the plural (not to be confused with ‘contemplation’, alias ‘contemplative meditation’, practised in the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christian churches, which is the Christian equivalent of what in Eastern religions is translated as ‘meditation'). Steiner’s exercises include visualisations and are intended to help the practitioner achieve contact with planes beyond the physical, with a concomitant emphasis on character training.

It seems there is some disagreement as to the level on which the Akashic record is located—“you can’t expect experts in any field to agree” is Teal Swan’s comment. Mental and visualisation exercises from Higher Worlds are quite commonly used by long-term Steiner affiliates, and are understood to produce identifiable results. The late Miss H, Director of Camphill Delrow near Watford, where I worked in the mid-1970s, told us of a buzz of energy which the exercises produced at the end of her nose, which indicated to her that she was on the right track. However, no aficionado of Steiner has ever developed an ability to ‘read’ the Akashic record; not even in part, so far as I am aware.

The term ‘Akashic record’ appears to have been coined in Theosophic circles in the late nineteenth century. I accept, or at least tolerate, the idea myself (though not the far-back extension of it as used by Steiner), in the sense of its being an unproven, though possibly useful, hypothesis. The idea is said to have been cited in various Biblical references, in those Old Testament texts which refer to records in “the Book of Life”. The important point to note, however, is that a ‘reading’ of the Akashic record does not of itself constitute ‘proof’ of the facts read therein, at least not if we feel beholden to ideas of scientific method or historical evidence. Indeed, Steiner himself, at the end of Lecture 2, says as much:

[…] [I]t is at first extremely difficult to extract many things from the Script of the World—especially things of this nature! […] I cannot at all say that I am able today to say precisely what is in the Spiritual Script.

Nevertheless, concludes Steiner,

when you hear these words, you may feel an indication of what lives in me when I speak about the secrets which I would like to call the secrets of the so-called Fifth Gospel.

Thus—as happens over and over again when we try to close on some aspect of so-called “spiritual science” according to Rudolf Steiner—we encounter a nebulous morass.

So we see that Steiner himself produces no evidence whatever for his assertion that Jesus’ body was received into a crevice in the earth, which then closed over the body. This kind of assertion without evidence, supposedly taken by some sort of clairvoyance from the Akashic record, runs through large parts of the Steiner œuvre, the most notable exception being Steiner’s book “The Philosophy of Freedom, (transl. 2011), which is a philosophical approach to the psychology of perception (and not the most readable or concise, it must be said!).

Steiner did acknowledge that his insights should be tested—in various applications—for their efficacy, but many of his leading so-called clairvoyant insights are simply untestable. I personally have no recollection, during my involvement in Steiner employment, study, and some social life between 1974 and 1987, and again in social contacts in Aberdeen in 2004–2005, of any Steiner aficionado ever taking the view that Steiner might have got some things wrong. Such blind devotion constitutes a theocracy, the polar opposite of science in any meaningful sense of the word. A theocracy is not necessarily a cult in the pejorative sense of that word; but to maintain that one’s basic ideas, indications or assertions—including ones that are inherently untestable—are ‘science’ certainly is on the cultic spectrum.

Somewhere in the current literature on cults is the observation that no movement can be a ‘cult’: only a specific organised community, or group of communities, can be a cult or cultic, according to that view. My interpretation is that in the Steiner movement, we see the opposite: the ‘draw-down’ from the complex and sometimes inherently unprovable Steiner ideology adapts in different ways and degrees to practical life. In that sense, according to specific project and depending on the effectiveness with which it is managed, these draw-downs can be useful to the broader community. But the cornucopia of ideas at the back of projects, sometimes derived from patently unreliable sources such as readings from “the Akashic record” or other ‘supersensible’ reflections, barely adds up to “spiritual science”.

Science?

So, is ‘spiritual science’ ‘proved’ in practice through the extensive and diverse projects descending from Steiner’s work? Here, the evidence varies; and ‘proof’, as far as the Steiner world is concerned, proves to be a stretchable concept. Food and wine from Steiner-based organic horticulture, agriculture and viticulture can be tested through consumption: these compare well with other comparable produce, though the devotion applied in their production renders scientific comparison virtually impossible.

For over forty years, I myself have used various ‘alternative’ medicines, including anthroposophical and homoeopathic, and find them all effective though in differing degrees; and often, my own usage has been in a package of remedies which makes discrete evaluation difficult. In the UK, the generally dismissive attitude of the British Medical Association towards ‘alternative’ medicine, particularly towards ‘potentised’ remedies such as are used in anthroposophical and homoeopathic medicine, makes objective testing virtually impossible, as there is no agreed common methodology; quite apart from the blinkered attitude of the BMA towards so-called ‘alternative’ medicine in general.

Further, the Camphill Movement, it must be said, has had some notable success through provision of curative education in a supportive environment for mentally less able members. Dr Thomas Weihs, one of its founders (died 1983), was particularly noted for his work on childhood autism. His book Children in Need of Special Care (revised edition, publ. Souvenir Press, 2000) is a helpful introduction to the beneficial purpose and work of Camphill.

There is a downside. ‘The Camphill bully’ was how two ex-Camphillers-—co-principals of a Steiner-based ‘approved school’ (a British type of corrective school) where I worked for two terms—identified a clearly-identifiable personality trait among Camphill-trained staff (who are known, in a calque on the German term Mitarbeiter, as ‘co-workers’). In mitigation, the bullying and power-play, in my experience at the two Camphill communities where I worked prior to moving to the approved school, was staff-on-staff, never staff on vulnerable members. It did, however, contribute—substantially—to co-worker exhaustion, which obviously eroded the quality of nurturing presence which co-workers were able to provide for the more vulnerable. (Not all co-workers were Camphill-trained: many, including myself, had entered from a variety of other backgrounds).

Busyness

There was another typical downside I experienced at Camphill Delrow in the mid-1970s, and my experience was supported by the above-mentioned principals of a Steiner-based ‘approved school’, who had noticed it during their earlier work at Camphill Aberdeen. All spare time, i.e. evenings and most weekends, was expected to be occupied with some timetabled activity, whether teaching it or being taught. Thus, constant preoccupation militated against the very ‘village’ structure and ambience which Camphill villages were supposed to be supporting. Normal social life was simply impossible.

This oppressive feature augmented an overall feeling of being incarcerated within a totalitarian régime. The Camphill-trained staff appeared to accept this regime: indeed, they hardly seemed aware of it. While nominally the structure at Delrow was village and collegiate, in practice, the Director, the late Miss H, ruled with the aid of two lieutenants who reported back to her in secret. These two were listeners who conveyed back to Miss H any talk of reform or unhappiness among co-workers, and it was our impression that such talk was interpreted as rebelliousness.

While at Delrow, I managed, despite exhaustion, to achieve a major reform in nutrition and cooking for all residents, which had been of very poor quality. Miss H had a nervous collapse after reading my report and suggestions, and was off sick for a day—apparently the only time she had ever been off work during a Camphill career of some decades. Her only response to me was to glower when she passed me. However, my suggested reforms were quietly put into effect. Despite this, the episode became a milestone in my own deteriorating relationship with Miss H.

Exhaustion was the norm among most co-workers. After about a year of this oppressive régime, I finally, in the spring of 1976, felt some returning energy, with which I planned my escape. While still at Delrow, I secured an interview at a Steiner School (i.e., outside the Camphill structure) in Gloucestershire. During the interview, I was told that Miss H had given the principals a glowing report on me (which surprised me) and I was duly offered a job. However, I decided not to accept that particular post. Instead, I took the risk of moving out of Delrow, without a post to go to, into a YMCA in neighbouring Watford, in order hopefully to recover from exhaustion and devote myself full-time to my job search. Quite quickly, I obtained an interview at another Steiner School, Peredur Approved School at East Grinstead, and was afterwards offered a job as House Father from the autumn term, which I took.

During a tea break some weeks into the new job, the principals, Mr and Mrs Rudel, told me that they had received a very waspish verbal report on me from Miss H at a summer school which they and Miss H had attended. “I hear Paul Greenaway has applied to you for a job,” was Miss H’s opening gambit. It was partly on the basis of that bad verbal report that the Peredur principals had decided to offer me the job! Their reason was fascinating. Years earlier, they had themselves worked at Camphill Aberdeen when Miss H was there too, and they knew what she was like. That Miss H was now giving me a bad report indicated to them that I was probably all right. Clearly, after I had left Delrow, Miss H had felt free to vent her spleen regarding me, whereas when I had applied (shortly before leaving Delrow) to the Gloucestershire school, Miss H’s main aim had been to get rid of me, hence the earlier glowing report.

Many other co-workers, all non-Camphill-trained, left Delrow soon after me, all exhausted. Dr Anthony Daghenaar, a brilliant and broadly erudite Dutch anthroposophical doctor who had retired to Delrow but became appalled by Miss H’s bullying, left as soon as he could afterwards. (His experience, with other information, suggests that the worst problems in the Steiner movement—see websites below—may be more local to UK and US experience than shared with the continental European movement). Mr and Mrs Rudel at Peredur recalled how long-term Camphill co-workers liked to talk glowingly of big changes within Camphill, while the reality was no essential improvement, as the organisation seemed to be suffering from institutionitis and incapable of realistic and genuine attention to areas of failure. Idealist in-talk and over-filled timetables covered the blind spots.

Much later, when living in west Aberdeen near the original and now well expanded Camphill in the noughties of this new century, I renewed contact with Steiner-linked social life for a time (not solely Camphill). Two egregious examples (one triggering enduring clinical depression in a professional young woman) indicated that the bully tendency still continued—naïvely unnoticed and unremedied.

In the early 1970s, a Jungian analyst based in London, Kevin O’Dowd, was commissioned to do some research on the efficacy (in terms of fulfilling their defining articles of association) of western ‘ashrams’ (interpreted in a somewhat loose sense to mean residential communities of a largely non-monastic kind around some religious focus). His conclusion was that, in every instance he investigated, these structures eventually devolved into two groups of people who needed each other in symbiotic relationship. These two groups were:

- people who needed to dominate, and

- people who needed to be dominated.

Camphill-trained staff, formally known as co-workers, appeared to fit that study at the two Camphill communities that I worked in during the 1970s. People who did not fit this dichotomy tended to leave.

Prejudice?

Another aspect of Steiner’s ‘spiritual science’ has received some due critical attention, albeit not mentioned in idealist presentations. Here, I invite interested readers to do a little of their own research. Please see The Janus Face of Anthroposophy by Peter Zegers and Peter Staudenmaier. This carefully-referenced article builds on an earlier article which had elicited an ineffective response from an Anthroposophical source. Readers short of time should at least read page 3 (of what amounts to a six-page printout), along with end notes 43 and 44. The authors clearly substantiate very strong underlying racialism in numerous writings and teachings of Rudolf Steiner (though he was never a Nazi).

My own ‘road-test’ of another Steiner source supports the above. “Blond hair actually bestows intelligence,” said Steiner in a lecture, recorded in Health and Illness, vol. 1, transl. 1981, p. 86. The book includes several other passages of similar sentiment. Some argumentation is given to back up such seemingly weird statements, but it descends from premises or assertions that can only be seen by Steiner, often nebulous, and some of which must sound to non-devotees as sheer nonsense. Steiner’s defenders claim, reasonably, that racialism is not generally found in practice in Steiner-linked purlieus. Nevertheless, the strong latent racialism begs the question: Where else did Steiner go wrong? The myth of infallibility is broken, and with it the general notion of “spiritual science”.

Also worth consulting is Spotlight on Anthroposophy by Sharon Lombard (2003). Lombard mounts a general critique of Anthroposophy under headings according to subject area. Regarding Steiner-based schooling, she argues three points, on the basis of an extensive study of Steiner-based pedagogy and other writings, and of her own family’s experience of a ‘Waldorf’ (i.e., Steiner-based) schooling curriculum taught to a daughter who attended a Waldorf School in the USA:

- Her family and most of the other “esoteric-illiterate” group of parents and teachers in effect served as a “veil of ‘normalcy’” which hid the true underlying nature of the syllabus.

- Pupils are in effect “being passed through a covert mystery initiation corresponding to Steiner’s doctrine of the spiritual evolution of the Aryan”.

- The underlying mystery school initiation is hidden through the use of ‘doublespeak’. ‘Non-sectarian’, in effect, means ‘sectarian’; ‘scientist’ means ‘occultist’; ‘lecture’ means ‘sermon’; ‘verse’ means ‘prayer’; ‘science’ means ‘religion’, and so on.

Conclusion

Yes, Anthroposophy merits more than a superficial glance. Its faithful followers tend to be blind to the difference between proven (or at least plausible) science and inflated, pretentious conjecture, both of which can be found in plenty in Steiner’s work. To date, within the new Academy/Free Schools structure in the UK, three Steiner-based schools have been able to open as Free Schools: the UK Department for Education stated, in an e-mail of 14 August 2018, that there were no further applications pending at that time.

While there are commendable aspects of the Steiner legacy, including aspects of its school education, there is clearly a questionable side, too; yet necessary critique among Steiner followers is inhibited by their totalist attitude to the words of ‘the Master’. Due critical attention must therefore be applied from outside, particularly in the form of informed probing by appropriate regulatory authorities. Possibly, a little more research by Education Department advisers, or perhaps a culling of advisers, is called for?

Bibliography

(The author has previously written an account of the New Age in the United Kingdom: In the Shadow of the New Age: Decoding the Findhorn Foundation [UK shopping link], publ. Finderne Publishing, 2003, ISBN 978-0-953-7433-06. Reviewed by Frank MacHovec PhD in Cultic Studies Review, vol. 2, no. 3, 2003.)

- Rudolf Steiner Archives—The Fifth Gospel, Lecture 2, by Rudolf Steiner

- Rudolf Steiner’s Mission and Ita Wegman by Margaret and Erich Kirchner Bockholt, Rudolf Steiner Press, transl. 1977, p. 61, top.

Sadly, this important book was privately printed and is not available via inter-library loan from the British Library: it can be obtained only from an Anthroposophical library. The Library at Rudolf Steiner House, 35 Park Rd., London NW1 (near Baker Street tube station, tel. 020 7224–8398), has several copies in stock, which can be perused by anyone visiting the Library. To borrow a copy requires completion of a form, countersigned by either an existing member of the Anthroposophical Society, or a college or university tutor. Postage is payable if borrowed at a distance. - The Occult Establishment by James Webb, Open Court Publ. Co., USA, 1986.

- An Outline of Occult Science by Rudolf Steiner, transl. 2011, Rudolf Steiner Press, Forest Row. The same translation is also published by Steiner Books, USA. The same text, but an earlier translation by C.E. Creeger, was published in 1997 by Anthroposophic Press, under title An Outline of Esoteric Science.

- Knowledge of the Higher Worlds, by Rudolf Steiner, ‘classic’ translation by Osmond/Davy, Rudolf Steiner Press, 2004. The same text but with an altered title: How To Know Higher Worlds, transl. Christopher Bamford, 1994.

- The Philosophy of Freedom, by Rudolf Steiner, reprint of a translation by Michael Wilson, Rudolf Steiner Press, 2011. The same text but under different title: Intuitive Thinking as a Spiritual Path, Anthroposophic Press, 1995.

- Children in Need of Special Care by Dr Thomas J Weihs, revised edition publ. Souvenir Press, 2000.

- The Janus Face of Anthroposophy by Peter Zegers and Peter Staudenmaier, Waldorf Critics Articles—downloaded 14 April 2015.

- Health & Illness, vol. 1, sub-title: Lectures to the Workmen. These lectures were given by Rudolf Steiner in 1922 and translated by Maria St Goar, publ. Anthroposophic Press, 1981, p. 86. The British Library has a copy, as does Rudolf Steiner House Library (see second entry above).

- Spotlight on Anthroposophy by Sharon Lombard, Cultic Studies Review, vol. 2, no. 2, 2003; Waldorf Critics Articles—downloaded 14 April 2015.

Translations of Rudolf Steiner’s works listed above, including of Bockholt’s book, are as recommended by Rudolf Steiner House Library, Park Road, London NW1.

Internet references

Two useful sites are WaldorfCritics.org, also known as PLANS (an acronym for People For Legal And Non-Sectarian Schools), and WaldorfWatch.com, compiled by Roger Rawlings, with occasional contributions from other sources. While I disagree with Rawlings’ assertion that there is no such thing as clairvoyance, Rawlings does expose, under various headings—e.g ‘Steiner’s Blunders’—the complete lack of scientific or historical evidence for much of the material that Steiner claimed to obtain in this way.

These websites are factually backed, particularly for Steiner quotations, but need to be balanced by critical evaluation of the critics. Here, the website WaldorfAnswers.org leaves too much unaddressed. As regards the specific allegations of racism within Steiner’s work, an attempted rebuttal—in my view, missing out much and with its own weaknesses—is given in an article headed A Refutation of the Allegation of Racism against Rudolf Steiner by Richard House, a Steiner Waldorf teacher, in New View Magazine, a British Steiner-oriented periodical, Issue 68, Summer 2013.

In fairness, House does reasonably suggest that “anyone harbouring the slightest doubts” about Steiner’s alleged racialism should actually visit “a Steiner School [...] or a Camphill Community, or a bio-dynamic farm, or any anthroposophically inspired company [...] and reach [their] own informed conclusions”. However, House’s citing of what is known as “the Dutch report” (April 2000) is hardly conclusive, since he acknowledges it was carried out “under a mandate of the Anthroposophical Society in the Netherlands”, and we are not told who the rapporteurs were, apart from the chairman, or who selected them. The weaknesses of this Dutch report are strongly criticised, with referenced quotations, in two well-researched internet articles: the above-mentioned Spotlight on Anthroposophy by Sharon Lombard (2003) (Cultic Studies Review vol. 2 no. 2, 2003) and The Janus Face of Anthroposophy by Zegers and Staudenmaier (WaldorfCritics.org).

“It is certainly arguable”, writes House coyly, “that a small number of quotations are, indeed, somewhat problematic, even when taken in context […]”. Lombard speaks of having to decode “Anthroposophic doublespeak”, a view strongly supported in The Janus Face of Anthroposophy.

Image: Euskara, Wikimedia Commons | licence: CC BY-SA 4.0