Thirty years ago this lunchtime, I attended the only Monday chapel service ever held during my time at Rugby School, one of Britain's foremost public schools (by which in Britain we mean private boarding schools). In a state of shock, we sang:

Fight the good fight with all thy might!

Christ is thy strength, and Christ thy right;

Lay hold on life, and it shall be

Thy joy and crown eternally.Faint not nor fear, His arms are near,

He changeth not, and thou art dear;

Only believe, and thou shalt see

That Christ is all in all to thee.

This was not a regular schoolday Chapel service with the customary pep talk; those never happened on Mondays. Our housemaster, Malcolm Lee of School House, had just committed suicide that morning, and this had been his favourite hymn. On the last organ chord, without a word needing to have been uttered to make the arrangement, we School House boys remained standing as the rest of the School sat in the pews, and we filed out of Chapel first.

For all our unanimity of sentiment on 8 February 1993, we were not all paragons of Christian learning nor fine specimens of British gentlemanliness—these being the avowed aims of Rugby's noted early-Victorian headmaster, Thomas Arnold (whose policies were immortalised in Thomas Hughes' Tom Brown's School Days). The catalyst for Mr Lee's suicide had been a wretched incident over the weekend.

While I had been on leave-out for my grandfather's birthday, a Hooray Henry of the sixth form had seen fit to defecate in the bed of School House's general bullying victim of the moment, a music scholar of rarefied soul and "common" Norfolk accent. I had arrived back at the House to find the lad—who counted only me as a friend at this time—utterly distraught.

School House was intended as the praetorian guard of Rugby School, where the manliest and the brightest boys were trained in the same complex of buildings as the chapel, the oldest classrooms and the Headmaster's apartment.

The House had a particularly stern code of omertà, akin to what one might expect among the inmates of a Category A prison. One of the tutors told me, altogether in earnest, that he intended for us to become the élite. Nevertheless, when my friend's tutor knocked on my door that Sunday teatime to ask why he was beside himself, I knew that I was obliged by my Creator, my conscience and the school's own Anglican foundational ethos to tell him the truth. He stormed off ashen-faced to inform Mr Lee.

At bedtime, another of our senior Hooray Henries, chummy with the perpetrator and of similarly monied stock, took it upon himself to interrogate us all individually in the dormitory showers to ascertain who had transgressed the code of silence. I told him the truth, too, and he pulled a knife on me. Big for my fourteen years, I was not going to fit into one of the soiled laundry baskets to be tumbled down six flights of stairs, as had been done to the music scholar, so he progressed straight to the armed stage of conflict.

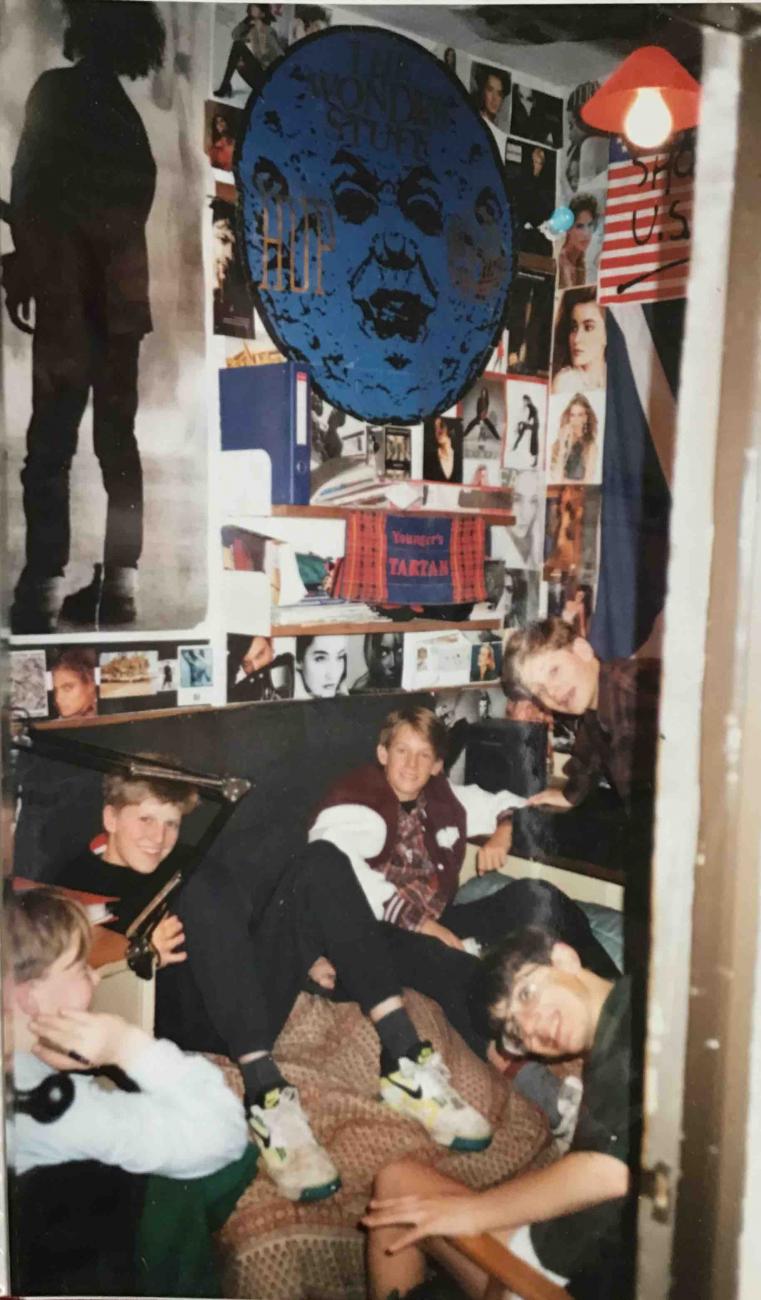

It was the easygoing Aussie in my year, Rob (the boy with the red-and-white jacket below), who intervened to prevent a stabbing.

It was because of Mr Lee that I felt no inclination to flinch from the blade. At the Christmas dinner two months previously, he had addressed us on something that I have never heard anyone brought up west of Budapest ever take as his theme before or since: the virtue of Honour.

At midnight, Mr Lee put the fear of God into us by unprecedentedly doing a spot tour of the dormitories. In hindsight, I surmise that he was taking his leave of his charges in the only way he knew, and that he had resolved to kill himself at dawn because he had lost control of the House. A former trainer of Pontypool Rugby Football Club, he was a passionate but not an eloquent fellow; the most endearing term in his repertoire was, "Oi!". To give praise, he would talk well of a boy in front of his peers.

The first time my mother took me to Rugby School, to be interviewed by Malcolm Lee, he evinced this disconcerting manner by saying, in view of my being a year younger than the rest of the intake—and not to me, but about me—"Well, he's obviously physically up to it; whether he's mentally up to it remains to be seen." For years, I imagined he was referring to the scholarship exam that I was to sit the next morning.

On mature reflection, I believe he was alluding rather to the fortitude required to withstand life in the pressure cooker. He will have known at a glance that I would be able to deal with fisticuffs both in the House and on the street with town boys (he was right; both kinds of confrontation were regular), but the school of hard knocks to which he was ultimately referring was the struggle to keep one's mind among scions of the British Establishment.

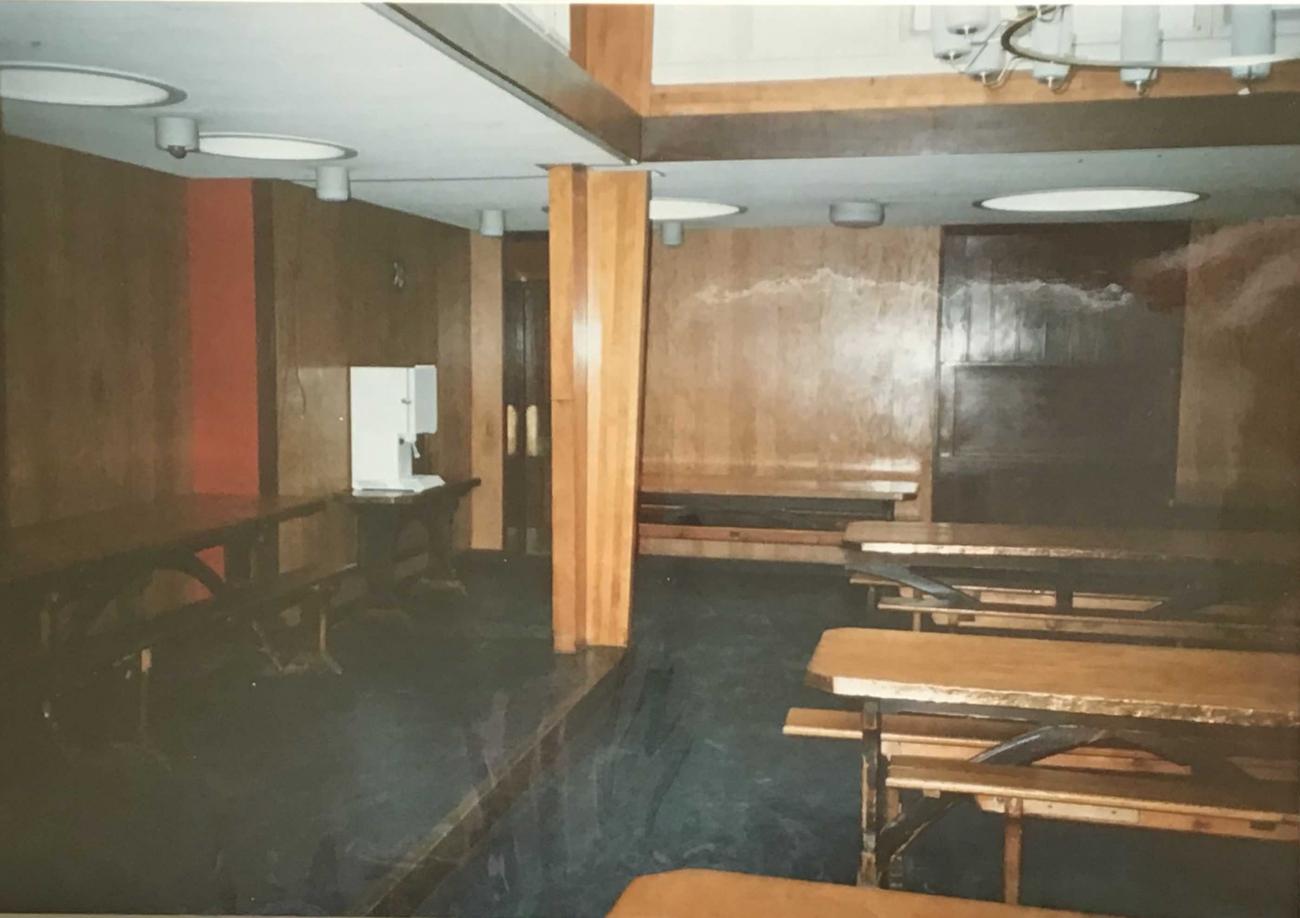

The facilities in School House at this time were rudimentary, but we didn't suffer for it. A teenage boy fresh off the rugby pitch will wash in anything and eat anything.

We ate at the tables seen below. School policy—and this was one of the secret weapons of institutions like Rugby in those days—was to bring the girls (who at this stage in the school's history were only admitted as sixth-formers) from their own boarding houses to the boys' houses for lunch and dinner, and to seat one tutor or visiting adult at each table, to ensure that conversation was not profane or jejune. On one occasion, Hywel Williams (of whom more anon) was seated at my table, and a boy piped up, "What's your favourite food, Sir?"

"Brains," he replied protractedly, with a wicked grin. "Nice, white, fluffy brains."

It had the desired effect; we started discussing devolution policy instead.

Two of the boys in my year with whom I got on best were Terence, from Hong Kong, and Ed, from an Anglo-Dutch oil family. Ed, like me, was a scholarship entrant. His sharp tongue was what got him out of most tight spots. He had a passionate hatred of nasty behaviour, an attitude which I imbibed with admiration, for it cost the slightly-built likes of him much more than it cost me. It was with Terence that I had debates over the nature of happiness, the rule of law and the most elegant qualities of women, over illicit tots of whisky.

These lads had lived in harsher countries than Britain, and I vicariously learned from them—and even more pronouncedly from other Rugbeians from a host of African and South Asian nations—that the constitution and governing ethos of a country made the difference between tyranny, anarchy and that sweet spot in the middle where there is just enough government, a spot known as peace. Terence looked up to Malcolm Lee a great deal and cried for him on the day of his death.

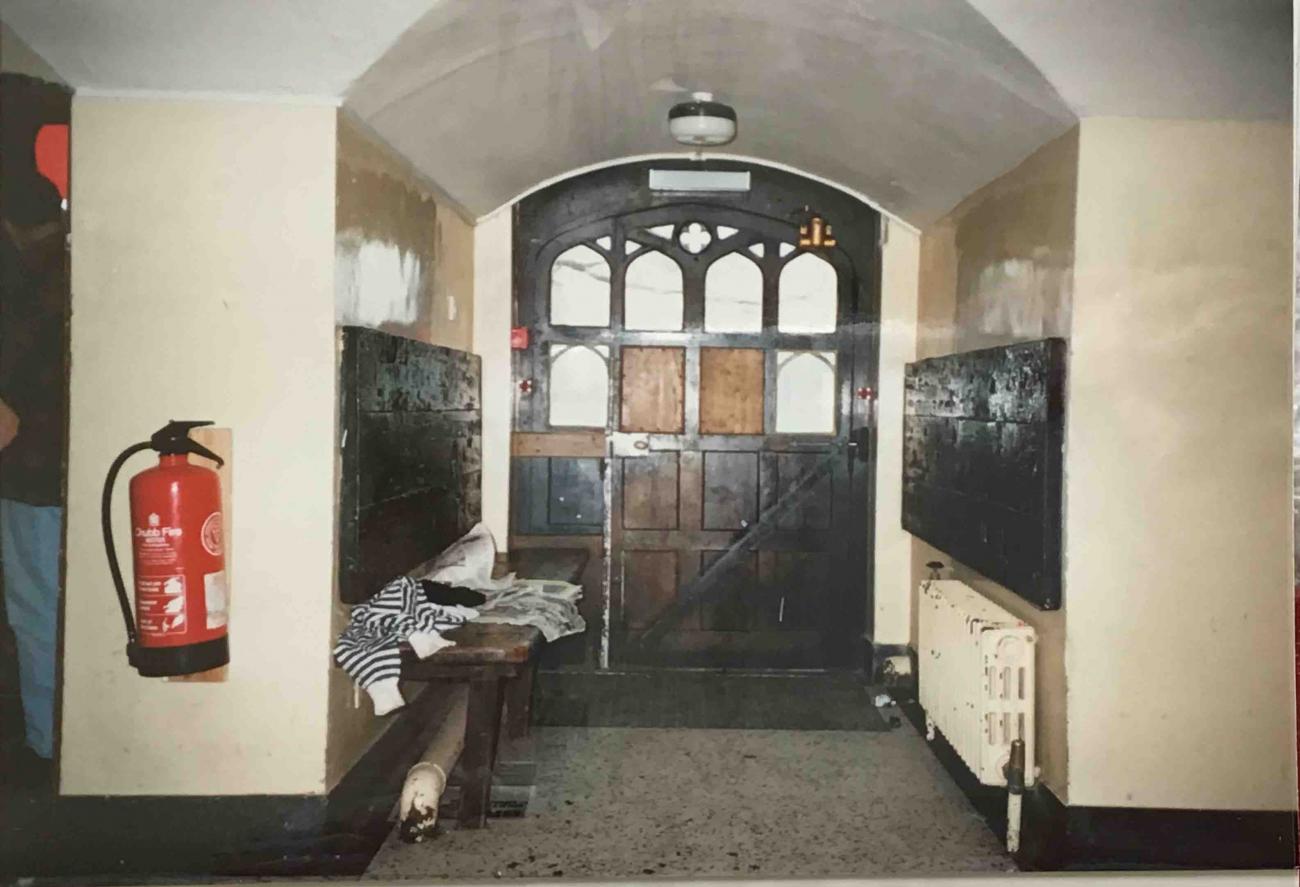

Toughening up was a daily occurrence. The moment when School House boys felt a lump rising in their throats—at least, those of my subterranean skill level in sports—was when they emerged from the below-illustrated door onto the Close. If you were wise about it, you could get your own back on bullies in the scrum.

What the below photograph reminds me of above all, however, is of a May day in 1993 when one of the lads pictured in the group photograph above made a casual comment while poring over my wall map of the world: "My parents will be somewhere around there now" (while pointing at a speck in the South Pacific). He hadn't seen them for a year or more, and he was hurting badly. It was his grandfather who came to pick him up for exeat weeks, and when he did, he barked, "Have you come in the Range Rover or the Merc?" I suddenly understood his drug habit and his acerbic manner. By sixth form, he had mellowed sufficiently to have adult conversations.

That photograph of the door to the Close reminds me of another seminal event in my Rugby School career. In June 1992, my father returned from being one of the many Scots wrung dry by the unspeakable financiers of Jersey to seek work in a less vicious industry. On a bench on the Close, he told me the barest outline then, sparing the detail for when I had grown up, of how the cabal that runs that Crown Dependency had threatened to plant images of child rape in his accommodation and suggested that they could arrange to have my mother and me menaced in his absence, in an attempt to make him give up the business he had perfectly lawfully started after leaving the London bank in whose employment he had arrived on the island.

Dad had grown up partly in a West of Scotland children's home; not the routinely abusive kind whose victims we champion on UK Column, but the other kind, where dedicated Christian matrons worked wonders with poor and unwanted bairns. This being his boyhood scene, Dad did what the louche financiers hadn't been expecting, and squared off. They fled.

It was while hearing of this from Dad that it first dawned on me that, with a care to my soul, I would have to be in the Establishment but not of it. That determination was sealed on 8 February 1993: I was going to live with Malcolm Lee's values, not with those that had been the death of him.

BBC cameras caught the School House of this era on a visit in 1988, three years before I came up to Rugby. At timestamp 4:20 in this documentary, Malcolm Lee is heard and then seen addressing a pair of exchange pupils from a Liverpudlian school. A minute later, we see Hywel Williams, a School House boys' tutor, in his grinning element; and then we see him giving a politics and philosophy class, but not before Ian Barlow has been featured drilling the Classics. The scene of him captured here is actually Barlow at his least harrumphing, but he jolly well made sure you knew your fifth declension ablatives.

Where did Malcolm Lee and Hywel Williams derive the resolve for their civilising labours among a preponderance of privileged young turds interspersed with a few apprehensive and timorous spirits?

They were brought up in the chapel-dominated scene of post-war South Wales. Hywel Williams (not to be confused with a namesake who has written for the press) was a Conservative—a rare bird in those valleys—and took a few months off in my first year at Rugby to stand for election in the hopelessly unwinnable constituency of Aberavon. At Malcolm Lee's evening remembrance service held a few days after his suicide, the Chaplain set out some memorabilia of Lee's youth, including books from the strong Christian upbringing that he, like virtually all Welshmen of his generation, had received.

The cymanfa ganu, or song assembly, is the jewel of the Welsh chapel tradition. Congregations come together, typically at the end of an annual practice season, to sing a schedule of hymns as outstandingly well as they can, to the glory of God and to instil faithfulness in the congregants. I often hear these swelling minor chords and their plaintive Welsh-language doxologies in my head when UK Column work is particularly challenging, and I am sure that Malcolm Lee and Hywel Williams did too when dealing with the most chinless of boy wonders. Here is an example recorded at Neath in 1986, just five years before I went up to Rugby. The hymn sung at 1 hour 6 minutes in this recording was not even composed until 1983; this is no fossilised tradition.

As for the first hymn sung here, the opening couplet of the last verse proclaims (in Welsh):

The debt has been paid

And hell has been trounced.

As is visible in the screenshot of the hymn booklet that the uploader of this recording has provided, some chapelgoer has pencilled in (in Welsh):

On the Cross.

There are more such remarks written in the margin against other couplets:

Faith in Jesus.

Beholding the love of God is beauty.

I give myself to Christ in view of His sacrifice.

Contemplate heaven and ignore the crowd here below.

The Lamb of God, the Only-Sufficient.

This faith was the boyhood formation of my late housemaster, and it is what made a man of him. It was a faith lived in houses of worship which, unlike Rugby Chapel, did not contain School Marshals advising boys like the sensitive music scholar and me, who had a habit of arriving five minutes early for a moment of prayer, "not to overdo religion". Here was the echo of a cry louder than the bray of the pink-cheeked Philistine.

The School Song of Winston Churchill's Harrow—the only other major public school that we Rugbeians regarded as non-effete, because they dared to face us on the rugby pitch—urges boys to look Forty Years On. (If you listen to the song from that link, don't miss the detail that the third verse and the Follow Up! echoed refrain after that verse are sung by the visiting fathers to their sons.) The Harrovians encapsulate the noblest public-school aim in their song as:

Strife without anger, and art without malice.

I am three-quarters of the way to forty years of adult life. So, three decades on, what is it that these two Welshmen taught me?

To face down bullies—calmly, with verbal dexterity and unyielding tone and body language.

To have faith in God and to insist on the founding principles of an institution. At Cambridge, GCHQ and now the international bodies where I interpret, it has been the same charade: the dinner ladies understand better than the graduate staff what the institution is supposed to be about and treat their fellow man with kindness, while the big names swan around with empty rhetoric inflated with barely-disguised contempt for the plebs, their noses perpendicular to the ground they deign to tread upon.

Brian Gerrish's disdain for cowardice in senior officers, David Scott's clarity that the oafs that run Britain are rich not in money but in money substitutes, Mike Robinson's loathing of City gents' predilection for starting wars, the propensity of all of us to study history and smirk at Hooray Henries—all was contained inchoately in what I learned from Malcolm Lee and Hywel Williams.

They helped train me for the work of UK Column, which itself is a re-honouring of the violated founding principles of the nation and its Crown. For they caused me to understand that I was already the intended article of production that the grandsons of City grandees with whom I rubbed shoulders were all too conscious that they could never become—at least, not without the humility that they so viscerally loathed as to prohibit the attempt.

I started this recollection with an English hymn, and I shall end with an equally stirring Welsh one: Pant-y-Fedwen (the tune name means "Birch Hollow") is regularly acclaimed as the finest hymn written in the world's greatest hymn tradition.

I thank God for Malcolm Lee, and if he were to clap his piercing eyes on me this afternoon, I would be able to greet him with, "Fighting the good fight, Sir."

And today, I have done what I was too immature to do in 1993: I shed a tear for Malcolm Lee, finally understanding that he did not fail at all. It was the oafs who failed.

My object will be, if possible, to form Christian men, for Christian boys I can scarcely hope to make.

Thomas Arnold, Headmaster, Rugby School (1828–41)