A fuller version of this article was earlier published by the Hardwick Alliance for Real Ecology (HARE).

As the chattering classes focus on Harry and Meghan, the make-or-break issue at the Coronation concerns the Coronation Oath that Charles takes tomorrow, on 6 May. For although academics at University College London’s Constitution Unit asserted last year (p. 10) that ‘the weight of the oaths lie overwhelmingly in their symbolic significance,’ actually—according to a report last month (p. 5) by the House of Commons—the oaths and ceremony not only have religious and ceremonial significance, but also constitutional importance. It is the role of the Coronation Oath in constitutional matters that must be our concern now that the coronation is upon us.

Charles himself stated in 2021 that ‘if you become the sovereign then you play the role in the way that is expected’. So this article explores the key part played by the Coronation Oath in the British constitution; historical forms of the oath including that used by Queen Elizabeth II; and finally steps that should be taken to ensure that Charles’ oath is strictly constitutional.

Modern times, but keeping within constitutional bounds

A coronation ceremony for the monarchs of Britain is a custom that can be traced back more than 1,000 years. Central to the ceremony is the unction, the act of anointing a monarch with holy oil, an act that signals the conferment of God’s grace upon a ruler. Today, the United Kingdom is the only European monarchy to retain such a ceremony (Torrance, 2023)—and one might have expected that God’s grace would be conferred upon those who have upheld God’s laws. However, here we have a Sovereign and consort who have, unashamedly, committed adultery, and so we are in uncharted waters. What is more, we have an Archbishop of Canterbury whose approval of same-sex marriage has lost him the support of 75% of Anglicans around the world, mainly in Asia, Latin American and Africa.

Sticking to constitutional rather than religious matters, however, the most significant element in the Coronation is the Oath, in which the monarch swears to govern the peoples of the United Kingdom and Commonwealth according to their respective laws and customs: the only part of the ceremony that, according to Torrance, is required by law. So what should we expect to find in a given Sovereign's coronation oath? And what steps might Charles take to offer reassurances regarding the legal aspects, given the arguably problematic elements of a religious nature for his reign? We will take a look at historic precedents and then go down the rabbit hole as we confront disturbing anomalies in Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation oath.

Historic precedents

The record is clear. English kings from the tenth century, including William the Conqueror and his immediate successors Henry I, Stephen and Henry II are known to have bound themselves by a threefold promise:

- to preserve peace and protect the church;

- to maintain good laws and abolish bad;

- and to dispense justice to all.

Neither Richard I nor John issued coronation charters, but the Magna Carta, as it was reissued in 1216, was in effect a coronation charter (Richardson, 1941). If we then fast-forward to 1309 and the coronation oath of King Edward II, we find the earliest English coronation for which we have an official record (Hoyt, 1955, 353). Not only that, but Edward II’s oath largely remained the format for a coronation oath for nearly four hundred years until 1689, when the oath was recast by statute (Richardson, 1941, p.135). Significantly for us and for the coronation on 6 May, Edward II added a fourth promise:

- to observe the laws and customs of England.

Why is this relevant to us today? Well, according to the most authoritative jurist of the thirteenth century:

The English hold many things by custom which they do no hold by law [...] Kings need only to have allowed the custom for it to be granted.

(Bracton, fo. I, ed. Woodbine)

These words bring the Magna Carta within the ambit of customs and, in so doing, assert people’s rights as ‘freemen’, alongside the right to a trial by jury (article 39). The Magna Carta also allows lawful rebellion by 25 barons (article 61), a right invoked in 2001 and still in force. So, given the centuries-long span in which monarchs have sworn to observe the ‘laws and customs’ of the realm, there would need to be good reason for Charles not to swear to maintain these, too.

Closer to home, there are lessons that Charles can learn from his mother’s coronation. Not least, the need to avoid the disturbing anomalies that—surprising though this may sound—call the legality of her coronation into question.

Anomalies in Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation oath

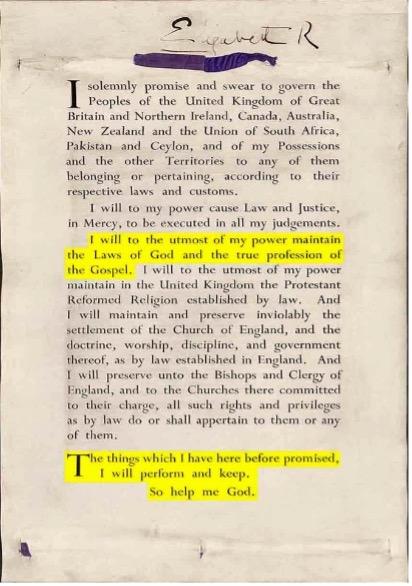

The young Queen’s coronation was a televisual spectacle, beamed out to an audience of twenty million at a cost today equivalent to around £19 million. She followed in Edward II’s tradition and swore to maintain the ‘laws and customs’ of her territories and to cause law and justice to be observed—but, despite the splendour of the occasion, her signed oath was rarely seen until 2022, when it was digitised for the first time to mark the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee.

As you can see from the image of the oath (below), the Queen signed her oath at the top of the document, rather than underneath the text, as would be more normal. Moreover, she added an underline beneath the first three letters of her name. There is also a ribbon below this signature, which begins on the left side of the document and then comes to an abrupt end at the same point as the line beneath her signature.

Why is this strange? Well, when I first looked into the matter in June 2022, most of the footage from the time obscured the view of Elizabeth II signing the document. However, eventually, I found footage that clearly revealed the signing of the oath, and this shows her adding a long flourish beneath her name. When I presented my findings at a Questioning History conference in December 2022, the audience was unanimous in likewise perceiving a discrepancy between the short line beneath the signature on the digitised oath and the line extending along apparently the whole length of the signature in the video footage.

That was not the only discrepancy. For, before 2 June 2022, the only image available of the Coronation Oath showed a different form of ribbon, which starts at a different point than in the digitised oath. Here is an image of it with the digitised image below it:

Queen Elizabeth II's Coronation Oath—version 1

Queen Elizabeth II's Coronation Oath—Version 2 (digitised). Source: National Archives

The anomalies do not end there, however. For questions have been asked as to whether Elizabeth II’s wooden coronation chair contained the original Stone of Scone or not. This stone was seized in 1296 by England’s King Edward I from Scotland’s Scone Abbey following his victory at the Battle of Dunbar and since that time, all English and subsequently all British sovereigns have been crowned while seated above it.

Four students, Scottish nationalists, stole the stone from Westminster Abbey on 25 December 1950 and returned it to Scotland in the trunk of a car; and one of them, Ian R. Hamilton QC, maintained in three of his books that the stone weighed 4cwt (458lbs.). However, the stone that was in Westminster Abbey for the 1953 coronation, and subsequently moved to Edinburgh Castle in 1996, weighed 3cwt (336lbs.) according to Historic Scotland’s official booklet entitled The Stone of Destiny: Symbol of Nationhood, obtainable from Edinburgh Castle (ISBN 1–900168–44–8).

In September 2022, Historic Environment Scotland confirmed that the Stone of Destiny would be transferred to London for use in King Charles III’s coronation, after which it would be returned to the Crown Room at Edinburgh Castle. However, with possible discrepancies in weight and also in colour of the stone (some say that the original stone was black, not the current pale colour), doubts remain that the Stone of Scone used in the Queen’s coronation—and to be used tomorrow in Charles’—is the real one.

Achieving transparency

There is one further elephant in the room, and this concerns the late Queen’s willingness to add her consent to statutes in 1973 and 2001 that passed British powers to Brussels. Some asserted, and still maintain, that this was treasonous and that her period as a monarch ended when she signed the relevant statutes into being. Given King Charles’ support, whilst Prince of Wales, for the World Economic Forum in Davos—the words ‘The Great Reset’ appeared at the head of his Prince of Wales section of the UK Government website—it is important that he now disavows his allegiance to an unelected body beyond Britain’s shores, something that English and British monarchs have repudiated in statutes and treaties for long centuries, including Præmunire and the Bill of Rights.

In fact, historical precedent suggests a simple way of doing this. In the seventeenth century, William of Orange was not allowed to take the throne until he agreed to uphold a Declaration of Rights that was designed to protect certain rights and customs in his realms-to-be. So he and his wife, Mary, agreed to this, with his respective realms' parliaments enacting the Bill of Rights (England) and Claim of Right (Scotland) in 1689, restating the terms of the Declaration drawn up by an elected convention of elders. Perhaps, in the interests of transparency and in order to advertise Charles’ primary loyalty to the people of Britain and the Commonwealth, he and all future monarchs could swear a Declaration to remain politically neutral and not ally themselves with WEF philosophies.

For, though we may be living in 2023, we owe a debt of allegiance to monarchs in the past who set the traditions according to which the British constitutional system was established. Perhaps, In the interests of transparency and clarity, a leaf can be taken out of the book of William and Mary’s Bloodless Revolution.

References

Bracton, De Legibus et Consuetudinibus Angliae (ed. G.E. Woodbine, 4 vols.; New Haven, 1915–1944

Hoyt, R. (1956), The Coronation Oath of 1308, English Historical Review, 70 (280), 353–383

Hoyt, R. (1955), Traditio, The coronation oath of 1308: the background of ‘les leys et les custumes’, 11, 235–257

Richardson, H. (1941), The English coronation oath, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 23, 129–158

Richardson, H. (1960), Traditio, 16, 111–202