In my previous article for UK Column, How Bill Gates hijacked a failing pharma system and smashed it: A tale of incompetence, deceit, greed, and an unmitigated thirst for power, I dug into the smashing of the global pharmaceutical industry, with the UK being used as the testbed, and gave context on the rollout machinery for SARS–CoV–2 injections.

This article takes a deep dive into how Britain's drug and medical devices regulator, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), has been—and still is—preparing the ground for a pharmaceutical business headquartered in the UK with a global reach. The supporting evidence is taken from a recent MHRA symposium that I attended as a virtual delegate.

About the MHRA symposium

The MHRA symposium referred to was day one of a two-day hybrid conference on Good Manufacturing and Distribution Practice (GMDP).

About the audience

The target audience for a GDP symposium (focusing on distribution) will typically be regulatory, quality, and supply chain management professionals working for pharmaceutical pre-wholesalers, wholesalers, hospital and community pharmacies, together with related company organisations. A GMP symposium will attract an audience of similar disciplines, but from the manufacturing world.

Hopefully, it will not have escaped your notice that this is a very powerful audience to address with coded and subliminal messages about the future for medicinal products. Brainwash this lot, and you’ve got an army of fervent followers doing Bill Gates’ work around the world. What follows are the notes I took over the day, comments, and translations for the layman where relevant.

Time to burn a few brain cells

Before delving into the symposium content, we need to burn a few brain cells getting our heads around the basics of the biological distribution supply chain. Without some important fundamentals, non-specialist readers may not appreciate the finer points of what I observed and heard over the day. So here we go.

Pharmaceutical regulations lay down good practices that pharmaceutical companies must comply with when developing, manufacturing and distributing medicinal products. They are the law, not nice-to-haves, and are comprised of the following protocols:

• Good Laboratory Practice (GLP)

• Good Clinical Practice (GCP)

• Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP)

• Good Distribution Practice (GDP)

All four apply across the pharmaceutical supply chain, but the predominant elements are GMP and GDP. Below is a simple diagram of the UK distribution network. Pharmaceutical companies sell their products fully finished, ready for patient use. Wholesalers have never been allowed to change the finished product in any way.

Diagram taken from What Patients need to know about Pharmaceutical Supply Chains

Wholesalers purchase and take ownership of the products, making a margin when their products are prescribed by a doctor and dispensed in the pharmacy. You can see in the diagram how the whole thing makes a neat, joined-up distribution network. Historically, a wholesaler must receive an inspection—which, if successful, nets the company the award of a Wholesale Distribution Authorisation (WDA(H)).

Alliance Healthcare (soon to become Cencora), AAH, Phoenix, and Aurelius (formerly McKesson UK) are some of the larger wholesalers. They only deal in refrigerated and controlled-room-temperature products. They operate dual-use vehicles that hold their deliveries within the ranges +2°C to +8°C (refrigerated) or +15°C to +25°C (controlled room temperature).

It was clear from the outset that the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna frozen injections had to bypass the UK’s long-established wholesaler network. If these injections had instead contained the traditional inactivated or live attenuated vaccines, requiring only refrigerated storage and transportation conditions, there would have been no problem. Even then, there are still complications, as this excerpt from the Biopharma Cold Chain Sourcebook, 2011, explains:

Biological products are essentially perishable because they consist of organic matter and are therefore influenced by extremes of temperature and the actinic effect of light. Carelessness in the handling and storage of smallpox vaccine, for example, often results in such injury to the product that it becomes inert, although physically it may appear to be in perfect condition and is of recent manufacture. Smallpox vaccine should be stored in a refrigerator or someplace where the temperature does not exceed 50°F.

(Parke, Davis et al., p. 1919)

In today’s money, 50°F translates to +2 to +8°C. The mRNA jabs were frozen down to either -70°C or -20°C, which makes them a ticking time bomb when it comes to keeping them safe from illegal temperature excursions. Not only that, but the injections were only partially finished—it was left to untrained and inexperienced people to carry out the finishing operations.

I was keen to know what the MHRA had been doing to ensure that patients were kept safe, given such a radical diversion of practice. What I learned was shocking. As I drew up a seat on the day, it became increasingly obvious that this was a stage-managed performance. Coded messages were unveiled over the day, couched in patient-friendly language. Behind them were chilling relaxations of regulatory scrutiny. The longer the show went on, the more obvious it was that there were carefully constructed, unspoken messages underlying the regulatory diktats that are traditionally handed down from the podium at these events. This wasn’t about patient safety, albeit the words implied it.

The MHRA is a sovereign agency

We kicked off with the announcement of the MHRA having been a sovereign agency (wielding executive powers) since the UK’s leaving the EU on 1 January 2022. That meant the MHRA could pass its own laws, subject to parliamentary nodding-through of the secondary legislation measures required.

The first thought that popped into my mind was the need to ensure that any changes didn’t invalidate the UK’s ability to sell pharmaceuticals to other countries. The MHRA may be sovereign in the UK, but the rest of the world has its own rules on the standards and quality of products it buys. Unilateral changes to standards are incredibly risky to trade, especially since the UK has to remain fully aligned with the EU standards following Brexit.

Continuation with remote inspections gets the thumbs-up

Experience with remote (virtual) inspections during Covid–19 was not entirely convincing, but we were told that they were to be continued as part of a hybrid inspection model. The tool of choice for the remote inspections would be the one that the MHRA used all through Covid–19: Microsoft HoloLens 2. The software also has application in healthcare. How convenient!

It is hard to fathom why supposedly intelligent staff at the MHRA depended on remote inspections during the Covid–19 crisis. Inspections only reveal potential issues when the inspector is free to dig into the nooks and crannies of a facility and interact closely with the staff therein. Not easy when the inspector is ensconced behind a desk hundreds of miles away, watching it all on camera!

Fewer inspections henceforth

We heard that the rules on inspecting wholesalers, and other organisations in with licences to handle medicinal products in Britain, were moving to a régime of risk-based inspections. In layperson’s terms, the MHRA would decide what facility to inspect based on their assessment of risk, rather than mandatory inspections on fixed intervals. Risk is a very subjective matter to define without resorting to the subjective thoughts of given human beings.

Along with that, inspections would move from a site-based to licence-based paradigm. This is quite a technical point, but the bottom line is that the MHRA could use it to justify not inspecting sites that it didn’t wish to. We were told “further details would be available through the usual channels.” That’s code for “you’ll need to pay for another symposium to find out.”

Confidential sites (!)

The next shocking revelation was the operation of confidential sites. We were told that GDP certificates printed on paper were being phased out and the database MHRA-GMDP would be the source of GDP certificates (which constitute proof that a company has a WDA(H) licence). If a GDP certificate could not be found for a site of interest, then it could be because it is a ‘confidential site’. From now on, we are to e-mail the MHRA to find out.

New GDP inspectors attending the symposium

There were several new GDP inspectors at the symposium, and those in the room were invited to introduce themselves. Apparently, they had been trained on the remote system only. That prompts me to raise something from my professional experience with the MHRA. From 2011, the MHRA has been haemorrhaging metaphorical ‘adults’, who are being replaced by juniors.

In 2010, I was a speaker at the Global Outsourcing Conference (GOC) co-sponsored by the FDA and Xavier University. Subsequently, I was invited to co-chair the 2011 conference and retained that duty until 2014. A speaker from the MHRA was on the agenda of this American conference every year. In 2011, it was Richard Andrews, Operations Manager. Andrews left the MHRA in March 2020, to join the world of consultancy. In 2012, the British speaker was Rachel Carmichael, who also left the MHRA a few years ago to join the world of consultancy. Then, in 2013, it was Mark Birse, Head of MHRA inspections. Birse, for his part, left the MHRA a few years back—in order to join the world of consultancy.

In 2014, the British invitee was David Churchward. Churchward left the MHRA recently to join Lonza as Global Head of Sterility Assurance, Cell and Gene Technologies. Lonza manufacturers the mRNA drug substance (active ingredient) on behalf of Moderna.

MHRA bins legislation aimed at keeping patients safe

We heard that the Falsified Medicines Directive (FMD), 2011, had been binned (placed in the trash, for US readers) by the MHRA. For those who don’t know, FMD 2011 was EU legislation passed to help keep patients safe from illegal goings-on in the supply chain. The need for it arose from an incident in 2007–2008, when a tragic event occurred that shocked the world into realising that pharmaceutical supply chains had the potential to kill and maim unsuspecting patients.

A blood thinning agent, heparin, had been adulterated due to the product license holder (Baxter) procuring a toxic substance that had been illegally substituted for the genuine registered material. The adulterated product was found to have caused nine patient deaths and 574 serious adverse events (SAEs). The full account of this has been documented in the report After Heparin: Protecting Consumers from the Risks of Substandard and Counterfeit Drugs, authored by PEW Health Group.

Given that the legislation is still in place in the EU and a similar act is in place in the US, we are bound to ask why it has been dropped in the United Kingdom. Patient safety was supposed to be the MHRA’s highest priority, or so they were saying.

A step change in criminal investigations

The recently-appointed head of the MHRA’s Criminal Investigations Unit, Andy Morling, took the podium and announced he had previously worked at the Food Standards Agency, being appointed there in 2015. His official biography notes:

He has spent the majority of his career working in these areas for HM Revenue & Customs, the Serious Fraud Office, the Serious and Organised Crime Agency, and latterly the National Crime Agency, where he was a senior intelligence lead.

Morling has been brought in to make a step change in pharmaceutical crime over the next three years, symposium attendees were told. Technology was going to be key in gathering intelligence. Microsoft technology, of course.

Compliance monitors—MHRA to outsource inspections

The MHRA has a pilot scheme aimed at bringing independent consultants into the regulatory compliance process. MHRA briefers at the symposium were at pains to deny any potential conflicts of interest, justifying their argument by reference to the controls that they said they would be establishing. The pilot scheme is found online at the UK Government Compliance Monitor (CM) Overview and Application Process, and it states:

From April 2022, the MHRA will be running a pilot scheme to monitor companies that fail to comply with Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) and Good Distribution Practice (GDP) and are referred to the Inspection Action Group (IAG) after an inspection that has resulted in the compliance escalation process being initiated.

The MHRA’s Inspection Action Group (IAG) has wide-ranging powers that already exist in the regulations (the regulations written down in the Orange Guide; the ones that live in the physical world). The suspicion that sprung to mind is that the IAG no longer exists. No action has been taken in its name over the last three years (which is the normal duration of a British Civil Service appointment to a given post), so there has been a full churn: all its staff will presumably either have left or been redeployed.

After a couple of searches on the internet, I found a company that had set up as a Compliance Monitor under the name TM Pharma Group Limited. The business founder was former MHRA inspector Tracy Moore. I recognised the name somewhat, so I looked up an MHRA organogram. Sure enough, Tracy Moore had been an Expert GMP Inspector until recently!

This led me to a path that I didn’t want to go down—but I did, and found evidence of strange, unexplained goings on. We can see from the organogram that Tracy Moore was in the Inspection, Enforcement & Standards Division of the MHRA, which was headed at the time by Michelle Yeomans, Unit Manager, Inspectorate Operations.

That was a name I had seen before; and, when I checked back to the consultancy that Richard Andrews had moved to, there was Michelle Yeomans, MSc, EPiC Operations Manager and Senior Consultant. The Deputy Director and Group Manager for Inspectorate & Process Licensing, Dr Andrew J Gray, left the MHRA four months ago to join big-pharma firm Amgen, as Director, Global Regulatory and R&D Policy.

Rules for importing goods into Great Britain to change

We learnt that a new function had been created during Covid–19, known as an RPi. RP stands for Responsible Person, and that is a long-established role. It is basically someone who takes responsibility for quality at a licensed wholesaler. RPi, on the other hand, is a newly-created separate individual post-holder with responsibility for importing goods from outside Great Britain, including from Northern Ireland. This role was to be a permanent feature from now on.

I had to rack my brains to work out how this was part of the overall plan. It clicked eventually. Traditionally, under regulations, holders of a WDA(H) are only allowed to buy fully-finished medicinal products from the companies selling them. This is not a problem for the traditional wholesalers outlined above. There is, however, a company business model known as a pre-wholesaler. Pre-wholesalers sprung up in the late 1990s, offering pharmaceutical companies logistics services for a fee, as a temporary alternative to selling direct to wholesalers.

This arrangement allowed the pre-wholesalers’ pharma clients to keep ownership of their finished products before selling them into the wholesaler network. As I thought back to the original British authorisation for the Pfizer/BioNTech Covid injections, I remembered a reference to a company named Movianto, to be involved in distribution logistics:

In the United Kingdom, the vaccines will be delivered to designated NHS bodies or NHS contractors that have capacity to hold the vaccines at ultra-low temperatures, expected to be, but not necessarily, Movianto (in Scotland, England and Northern Ireland) and the Welsh Blood Service.

Another search revealed that Movianto had been acquired by a pan-EU pre-wholesaler, the Walden Group. Hence that comment in the UK Government authorisation: “but not necessarily”. With an RPi post in place, and with an ‘enabling’ MHRA invoking its sovereign powers, the RPi would have carte blanche to import part-finished products, as well as raw materials, chemical and biologic intermediates, and active ingredients. Walden would have full capability from abroad to undertake the storage, transportation, and import/export administration for the British market.

Single Trade Window

We learned at the symposium that the Single Trade Window was being established to avoid duplication of data, with the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) and the MHRA involved. More detail would be available “through the usual channels”, if you can afford it.

Covid flexibilities—shipping under quarantine

All the above are the dangerous goings-on referred to in the article headline; but there is more. The concept of Covid flexibilities is popular with the pharmaceutical trade associations, and they are wanting to adopt them as standard business procedure. In the explanations given at the symposium of the Covid flexibilities that had been operating (and still are), there was one bombshell of an admission.

Companies shipping products into the UK were allowed to ‘ship under quarantine’. That means as soon as the goods were produced, and before testing had been completed, they could ship into the UK. This was on the basis that the UK receiving company put a hold on the product until testing had been completed. It would be incumbent upon the shipping company to inform the receiving company once testing had been completed, and what the result was.

It is for the MHRA to prove me wrong on this, but my take is that since this arrangement is going to have to be agreed in practice between an EU-based shipping company (say, BioNTech’s facility at Puurs, Belgium) and a British receiving company, there has to have been mutual agreement behind the scenes to dispense with any dependance on the results of testing. Given the speed-of-science manufacture of the Covid injections, it is not only plausible that testing should be dispensed with globally, but more to the point, with a shipping-under-quarantine model, it would be the only way to achieve distribution deadlines.

This leads to the bigger picture

If the bigger picture does indeed, as I am now suspecting, include shipping under quarantine at a global level, then we know how the billions of Covid doses got out so quickly. Normally, the lead-time for completion of quality control activities following production of products and materials is at least weeks, but often months. On the other hand, with free rein for supply chain producers to make and ship, the lead times are collapsed immeasurably, along with safety. Whoever sanctioned this is guilty of gross negligence at the very least—lawyers may have a more damning name for it.

UK Government wants to be number one in the world for investment in life sciences

As we saw in my previous article, the UK Government has long nurtured the vision of becoming number one in the world of life sciences, although that vision has gone through various iterations over the past decade or more.

What you now know from this sequel article is that the UK Government has been using foul means, not fair, to achieve that vision. My analysis is that Crown ministers have been seduced by the pharmaceutical players, such as Vallance, Gates, et al., into believing that gene therapies are nothing less than the future of medicine. In fact, the development and manufacture of gene therapies is still in its infancy, as an article of mine in TrialSite News, entitled Gene therapy—is it really a sound investment prospect?, explains.

This wooing has brought about the construction of a global pharmaceutical business headquartered in the UK, with the following working parts:

Regulatory: MHRA and the self-styled International Coalition of Medical Regulatory Affairs

Sales and Marketing: the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, with its Global Heath arm headed by Trevor Mundel; and global regulatory enablement courtesy of Ian Hudson, with the WHO providing the scaremongering.

R&D and Clinical Trials: Advancing cell and gene therapies through powerful collaborations

Manufacturing: Lonza and Catalent Pharma Solutions (mRNA); Oxford Biomedica and Wockhardt (viral vectors)

Clinical research: ICON (of Brook Jackson/Ventavia fame)

Transport, storage and distribution (import/export): Walden Group (Walden acquired UK’s Movianto in 2020). As we saw above, the UK authorisation of the Pfizer/BioNTech Covid jab stated in terms: “In the United Kingdom, the vaccines will be delivered to designated NHS bodies or NHS contractors that have capacity to hold the vaccines at ultra-low temperatures, expected to be, but not necessarily, Movianto.”

Enterprise software solutions: Microsoft Azure Digital Twins; Healthcare; Microsoft HoloLens 2 (on a national pilot scheme as of 2021); Microsoft Purview Compliance Manager, etc.

Quality Compliance: Independent consultants called Compliance Monitors: TM Pharma and EPIC-Auditors.

In conclusion

The MHRA Delivery Plan underlines the massive changes that are coming up, and the symposium that I attended was just one vehicle being used to cement it in place.

As luck would have it, the keynote speaker, although he was a no-show for the GDP session, was included in the recordings provided to participants later. James Pound, Deputy Director, Standards and Compliance, at the MHRA had no slides and read from a script. I managed to record it for the benefit of UK Column readers—here it is, straight from the horse’s mouth. Dr Pound’s own request was to share it far and wide, so that is what I’ve done.

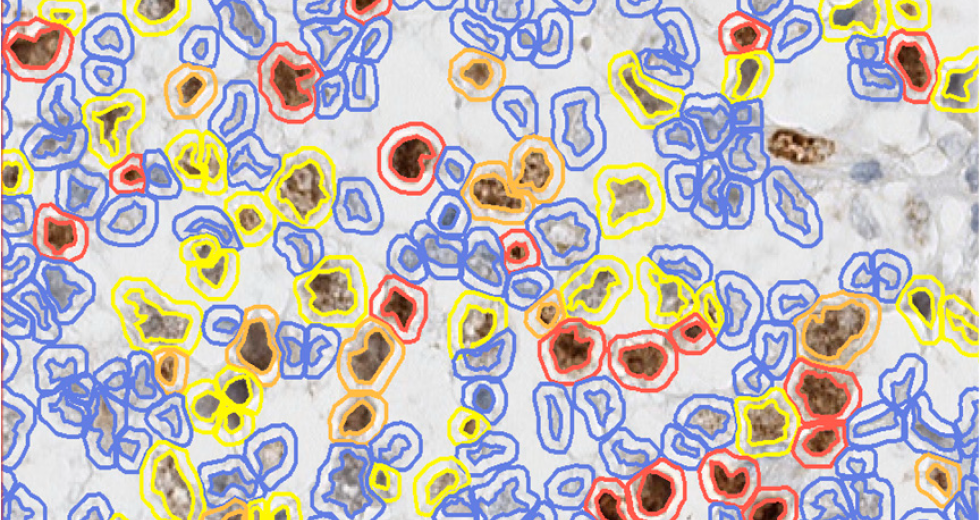

Article image: Wikimedia Commons | licence CC BY 4.0