The subject of lockdowns during the Covid crisis still remains a very controversial subject. There has been very little serious study into the harms of this policy. In the USA, however, Johns Hopkins—a university intimately involved with the worldwide Covid phenomenon—produced a research paper which studied the potential beneficial effects of lockdowns. The evidence base was considerable:

This study employed a systematic search and screening procedure in which 18,590 studies are identified that could potentially address the belief posed. After three levels of screening, 34 studies ultimately qualified. Of those 34 eligible studies, 24 qualified for inclusion in the meta-analysis.

The main conclusion was that “An analysis of each of these three groups support the conclusion that lockdowns have had little to no effect on Covid–19 mortality.” And further, “Specific NPI studies also find no broad-based evidence of noticeable effects on Covid-19 mortality.” The study’s final conclusion was (emphasis added):

While this meta-analysis concludes that lockdowns have had little to no public health effects, they have imposed enormous economic and social costs where they have been adopted. In consequence, lockdown policies are ill-founded and should be rejected as a pandemic policy instrument.

Despite this, there are worrying rumours that lockdowns remain one of the go-to options with regard to pandemic response for states in the near future. What’s more, some studies in the US go as far as to minimise the negative effects of lockdowns on people’s health. For example, the authors of a research paper published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) entitled The psychological impact of Covid pandemic lockdowns state the following:

The psychological impact of Covid-19 lockdowns is small in magnitude and highly heterogeneous, suggesting that lockdowns do not have uniformly detrimental effects on mental health and that most people are psychologically resilient to their effects.

But just how true is this? Anecdotal evidence and common sense suggest that the opposite is true. In recent years in the Western world, we have observed with tedious regularity that governments do not tolerate criticism of their policies, and have found effective means of silencing reputable critics. The controversial subject of lockdowns is no exception, and so authoritative studies examining the true damage to people’s health is hard or impossible to find, apart from cover-up pieces as cited above. Thus, we have to look further afield to gain insight into the real damage caused by lockdowns on people’s health.

Lockdowns wreck animals

To do so, I examine two very large studies, which—falling as they do outside of Covid policy—are very unlikely to have suffered from the censors’ whitewash. So, while the above-mentioned NIH paper may attempt to minimise the human cost of lockdowns and offer politicians an illusory fig leaf to protect their culpability, we shall see that the truth is far worse than many people feared.

When wild animals are taken out of their natural environment and placed into captivity, they begin to suffer from psychological stresses causing a variety of illnesses; these have been studied in a scientific paper entitled Chronic captivity stress in wild animals is highly species-specific. To cite the paper:

The stress response consists of the suite of hormonal and physiological reactions to help an animal survive potentially harmful stimuli. The adrenomedullary response results in increased heart rate and muscle tone (among other effects); elevated glucocorticoid (GC) hormones help to direct resources towards immediate survival. While these responses are adaptive, overexposure to stress can cause physiological problems, such as weight loss, changes to the immune system and decreased reproductive capacity.

The authors go on to say:

In this review, we focus on captivity’s effects on mass (one of the best-documented outcomes of chronic stress), GC concentrations and the immune, reproductive and adrenomedullary systems.

And later on, it is stated:

These studies on baseline GCs together demonstrate a pattern wherein approximately half of species appear to adjust to captivity. Although some species seem to take longer to acclimate to captive conditions than others, it appears that many species will eventually show a reduction in GCs after an initial peak.

In other words, in animals, the damage on approximately half of the captive individuals becomes mitigated after a lengthy period of time. It was also found that captivity had a marked effect on the immune system:

Changes in the immune response with chronic stress are thought to be most strongly tied to GC release. However, the impacts of GCs on the immune system can be complex. In the short term, GCs typically induce an immune response, while they can be immunosuppressive over the long term.

Thus, captive animals are far more likely to suffer from a wide variety of diseases including cancers, than their free counterparts, especially over time.

Furthermore, it was found that captivity had a negative effect on the reproductive systems:

The reduction of reproductive capacity might be tied to GC levels. GCs can be powerful suppressors of reproductive steroids (Sapolsky et al., 2000). Prolonged GC exposure can lead to decreased production of testosterone or estradiol, which can then have downstream effects on gonad development, egg maturation, sperm production and behaviour.

A variety of other damages were recorded on the captive animals:

Captivity can lead to various pathologies. In a histological study of mouse lemurs that died spontaneously in captivity, lesions in the kidney were strongly correlated with captivity duration and with adrenal size (Perret, 1982). The investigator also concluded that cardiac disease may result from chronic adrenomedullary stimulation, although they did not measure hormone concentrations directly (Perret, 1982). Similarly, herring gulls developed amyloid deposits in the blood vessels of their spleens after 28 days in captivity (Hoffman and Leighton, 1985). There may be many more hidden anatomical changes resulting from captivity, but few studies have looked for them.

Finally, recent data indicates that captivity can have profound effects at the DNA level. Bringing house sparrows into captivity resulted in an approximately doubling of DNA damage in red blood cells (Gormally et al., 2019). The impact of this damage on the individual remains to be determined.

And, perniciously:

The physiological changes caused by captivity can persist even after animals have been released back into the wild. Chukar partridges that were held in captivity 10 days and then released to a new location than where they had originated had lasting changes to their GC regulation (decreased negative feedback for at least 30 days, Dickens et al., 2009a). Red foxes that were kept in captivity for 2 to 8 weeks were less likely to establish a stable territory upon release than foxes that were caught and immediately released (Tolhurst et al., 2016). River otters kept in captivity for 10 months had lower survival than otters not kept in captivity (Ben-David et al., 2002). The captivity effect was strong enough that crude oil ingestion (mimicking the state of oiled otters in rehabilitation) had no further effect on survival (Ben-David et al., 2002). Rehabilitated barn owls (Fajardo et al., 2000) and guillemots (Wernham et al., 1997) had much shorter life expectancies than wild birds.

Our Eurasian ancestors learned methods to mitigate the effects of enforced captivity due to being forced to sit out harsh winters during the last Ice Age. Surviving the Ice Age summers was bad enough, but the winters were far more extreme. Snow lay thick on the ground, so getting about was slow and exhausting work. Additionally, there was always the risk of being overwhelmed by hungry packs of powerful cave hyenas, a ravenous cave lion or the dreadful homotherium. The cave, with its fire and the family, was the safest and warmest place to be. However, day after day, month after month, it was terribly boring.

It was in such a cave, in the Idrijca Valley in modern-day Slovenia, that a 70,000-year-old cave-bear flute was found, the oldest musical instrument that we know of from anywhere in the world. Music generally has a way of making us feel good, and even causes us to involuntarily move our limbs, tap our feet, or even dance. Music tends to promote happiness and may help to ward off boredom and depression. Then, from 40,000 years ago, cave paintings became increasingly common. All these were ways of creating homemade entertainment. Even earlier, European ancestors were creating fashion objects, beads for ornaments and even statuettes—all found in caves.

These absorbing and entertaining activities helped our ancestors to deal with the winters that kept them imprisoned for up to six months at a stretch. Crucially, these people lived in family groups and so had each other for support. They could converse, share ideas and tell stories. All this helped our ancestors to deal with the harmful effects of imprisonment on their health.

Lockdowns wreck prisoners

Fast forward to today: we impose solitary confinement on individuals as a punishment. Much study has been done both on people who have been subjected to solitary confinement, not least by the Prison Policy Initiative. They state that researchers have ascertained beyond any doubt that those who have undergone solitary confinement:

- a) suffer severe and often permanent damage, and

- b) die prematurely, even once liberated:

The effects of solitary confinement can be lethal. Even though people in solitary confinement comprise only 6% to 8% of the total prison population, they account for approximately half of those who die by suicide.

Solitary confinement has been shown to cause permanent changes to people’s brains and personalities. In addition, the part of the brain involved with human interactions physically shrinks. Like an unused muscle, it atrophies. Deprivation of contact with other people provokes feelings of distress, exclusion and rejection, also known as social pain, which can be just as debilitating as physical pain.

Prisoners subjected to solitary confinement have a tendency to develop a psychosis that is characterised by an inability to tolerate ordinary things such as the sound of plumbing. Such intolerances include having hallucinations, panic attacks, difficulties thinking, concentrating, becoming obsessive, sometimes becoming harmful, and having problems with impulse control. Studies published of individuals such as Messrs King and Morris, who both underwent extended solitary confinement, are both revealing and highly disturbing.

The above listing of psychoses may ring some very loud bells for those people who have seen some of the more deranged self-made videos that circulated widely during and after Covid. (Normally, I would be expected to provide links to examples of this behaviour on social media, but I’m unable to, because before writing this article I was given a lifetime ban from Twitter for pointing out to Chris Whitty his complicity in the deaths and other harms inflicted on the British population as a result of the Government’s Covid injection campaign).

The lockdowns that were imposed on most countries during the Covid epidemic imposed confinement on everyone, and solitary confinement on some. Those unfortunate souls who lived alone—often, already vulnerable people—were subjected to solitary confinement, with all its inevitable health impacts, as identified above. It is not surprising, therefore, that lockdowns initiated an increase in suicides. All the concurrent effects listed on prisoners in solitary confinement were also visited on those individuals locked down alone.

The rest, who were locked down in family units, were relatively lucky compared to those who were alone. However, they were still exposed to the risks that were observed in captive animals: lowered immune system response, lowered fertility, increased levels of stress, and changes to DNA. But unlike their ancient ancestors, they could watch television all day long as a means of alleviating any boredom. All this free time also meant unlimited access to mainstream news broadcasts and government announcements. In short, they had become a captive audience for whatever messaging the state wanted to put out. Lockdowns also contributed to the breakdown of social bonds, due to every household living in isolation from its surrounding community, friends and wider family.

ONS complicity?

In conclusion, lockdowns achieved the following important goals. They:

- pushed the solitary towards psychoses and potentially suicide;

- coerced the rest of the population into enduring endless propaganda, particularly the young;

- weakened community bonds, so that people became more dependent on central authority;

- greatly increased health risks, including lowered natural immunity, lowered reproductive ability, elevated levels of stress, and deleterious effects on DNA,

- produced long-term negative effects on health, beyond the end of the lockdown period, leading to shortened life expectancies for many; and

- enhanced the risk of more serious consequences of Covid, due to lowered immune function, as well increasing the likelihood of spreading Covid.

Discussing the effects of lockdowns in this somewhat detached way overlooks the widespread pain, suffering and human loss that this policy is responsible for. Probably millions of families around the Western world have been negatively affected; the whole cost may never be calculated and laid at the feet of those responsible. But we can gain a tip-of-the-iceberg insight by looking at the excess suicide rate. The WHO keeps track of global suicide rates, or rather, it did until the Covid crisis. Conveniently, perhaps, for the WHO itself, it stopped publishing global suicide rates from 2019 onwards.

For the UK, we have documented suicide rates for the three years preceding the Covid crisis, for both sexes, of around 7.0 per 100,000 for the UK. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) published that in 2020 for the UK as a whole, we had a suicide rate of 10.0 and 10.7 respectively by sex per 100,000 in 2021. This represents an increase of 42% above the pre-crisis levels for 2020, and a whopping 53% in 2021. In England and Wales specifically, the total number of suicides was 5,583, which suggests that around 2,000 people may have committed suicide due to Covid lockdowns in 2020 alone.

The ONS, wary of betraying the Government with these figures, advises journalists to be cautious when publishing these statistics. In other words, please look the other way; nothing to see here. At the end of the page on 2021 suicide rates, the ONS even goes to the extraordinary length of denying any link between suicides and Covid. This is what the ONS publishes on the 2021 suicide page:

We saw a significant increase in the rate of deaths registered as suicide in 2021. This increase was the result of a lower number of suicides registered in 2020, because of the disruption to coroners’ inquests caused by the coronavirus pandemic. The 2021 suicide rate was similar to the pre-coronavirus pandemic rates in 2018 and 2019. The latest available evidence shows that suicide rates did not increase because of the coronavirus pandemic, which is contrary to some speculation at the time.

—James Tucker, Head of Analysis in the Health and Life Events Division, Office for National Statistics

They claim that the suicide rate of 2021 was similar to that of 2018, which directly contradicts the WHO data. The question is, who is telling the truth? The present ONS data does indeed show that there appears to be little increase in the suicide rate between the years leading up to the Covid crisis and the lockdown years. However, digging into the ONS suicide spreadsheet data more carefully reveals some crafty editing on the part of the ONS, which the ONS admits to. In the notes section of the suicide rates, the WHO admits:

The back series (all years from 2001 to 2020) has been refreshed to take account for late registrations, so figures may not match those previously published. Figures include all deaths that were registered by 31 December 2021.

No further explanation is given as to why excess numbers should be added to the figures before the Covid crisis; moreover, notably—and explicitly—the excess suicide rate does not increase the lockdown years in the same way. This looks and smells like a very clumsy cover-up on the part of the ONS to ensure that no blame for suicides is laid directly at the feet of the state. A superficial examination of the data will mislead the reader into believing that lockdowns were not responsible for an increase in the suicide rate.

And so, if we are to believe the ONS, there is no particular concern from the human health point of view at the prospect of reimposing lockdowns in the future. Timely corroboration for this finding—of the complicity of the ONS in camouflaging the Government’s direct responsibility in inflicting harms on the UK population—was given by Andrew Bridgen MP in his recently-published interview with UK Column.

They knew

Often, we read that lockdown was an experiment, yet this is not really true. The dangerous effects of solitary confinement on individuals have long been known by behavioural psychologists, who formed an important cohort in the Government’s panel of experts employed during and after Covid—although leading politicians may well proclaim ignorance of this field of study. The evidence suggests that behavioural scientists knew exactly what they were doing and what the consequences would be.

It is highly unlikely that any precise analysis of all the negative health effects of lockdowns will ever be published, because to conduct such an analysis, one would need carefully-monitored control groups, and these control groups would need to be supervised and examined prior to, during and after lockdowns. This would amount to little less than controlled torture, comparable with Nazi experiments on humans. This ethical barrier suits the state, because such studies would undoubtedly prove the state’s role in deliberately harming thousands, and quite possibly millions, of citizens.

In the absence of such proof, the above analysis assumes an even greater importance. For as long as the state can convince the population that lockdowns are necessary to combat pandemics, it may still be free to unleash wilfully wide-scale harm on the public. But if the public become aware of the conclusions of the above-mentioned Johns Hopkins research that lockdowns have virtually no positive impact on the spread of Covid–19, in conjunction with the fact that lockdowns in their own right have a massive impact on public health, then maybe there would be very little public compliance. And in such a case, what could the state really do? After all, we are the many and they are the few.

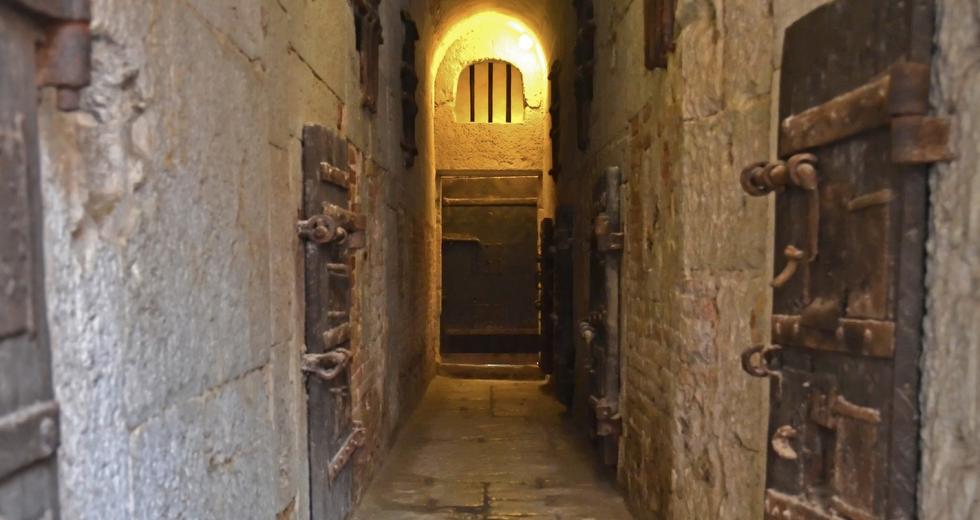

Main article image: Prison block in Italy | Photograph taken and owned by the author