In her speech "Britain after Brexit: A Vision of a Global Britain", delivered at the Conservative Party Conference, Theresa May made reference to a Great Repeal Bill which would have two effects. Firstly it would "remove from the statute book – once and for all – the European Communities Act". Secondly, it would "transpose 'the acquis' – that is, the body of existing EU law – into British law". According to May this will mean that "Parliament will be free – subject to international agreements and treaties with other countries and the EU on matters such as trade – to amend, repeal and improve any law it chooses".

The "acquis" to which Theresa May made reference relates to the European Doctrine "Acquis Communautaire". This means that when a power has been surrendered to a supra-national body, such as the EU, it can never be recovered by the member state. The effect of transposing all existing EU law into UK law via the Great Repeal Bill provides ample evidence of this.

In the four decades that have passed since parliament approved the European Communities Act the British people have been deceived and betrayed by governments and politicians of all political parties. Whenever a piece of legislation has been passed that angers the British public's sense of fair play and justice our politicians have always deflected criticism by laying the blame on the European Union. During this time-frame international law which originates within the institutions of the United Nations has either been transposed into UK law directly by our Westminster Parliament or has entered the UK via the undemocratic European Union. International law is framed by those who have never been elected into office by the British electorate and neither can they be removed.

In this article we will briefly examine the international law on public procurement to demonstrate just how hollow Theresa May's statement that we are going to be a "fully-independent, sovereign country" truly is.

The United Nations and Public Procurement

We have noted that the United Nations General Assembly resolution 66/95 of 9th December 2011 was "expected to contribute significantly to the establishment of a harmonized and modern legal framework for public procurement that promotes economy, efficiency and competition in procurement and, at the same time, fosters integrity, confidence, fairness and transparency in the procurement process". This UN resolution is referenced within the United Nations Commission on Trade Law (UNCITRAL) Model Law on Public Procurement, published in January 2014. UNICITRAL is the "core legal body of the United Nations system in the field of international trade law". UNCITRAL helpfully provides 69 pages of guidance on how the "enacting States will promulgate procurement regulations to fulfill the objectives and to implement the provisions of the Model Law".

The World Trade Organisation's Agreement on Government Procurement (GPA) requires that open, fair and transparent conditions of competition be ensured in government procurement. One of the key reasons for the 1994 Global Agreement on Public Procurement was to ensure that "the laws, regulations, procedures and practices regarding government procurement should not be prepared, adopted or applied to foreign or domestic products and services and to foreign or domestic suppliers so as to afford protection to domestic products or services or domestic suppliers".

The Agreement on Government Procurement has 19 parties comprising 47 WTO members. Another 28 WTO members participate in the GPA Committee as observers. Of these, 9 members are in the process of acceding to the Agreement. A block of European Nations which included the United Kingdom acceded to the 'GP Agreement 1994' on the 1st January 1996.

Obligations Contained Within the EU Procurement Directives

At the regional level, the EU Commission has dictated that "new rules have changed the way EU countries and public authorities spend a large part of the €1.9 trillion paid for public procurement". Amongst other perceived benefits, the EU Commission claims that these new rules will "prevent 'buy national' policies and promote the free movement of goods and services".

Their website reveals that from 18 April 2016, EU countries must have put in place national legislation conforming to three directives.

- Directive 2014/24/EU on public procurement, replacing Directive 2004/18/EC, for Public Sector Contracts;

- Directive 2014/25/EU on procurement by entities operating in the water, energy, transport and postal services sectors, replacing Directive 2004/17/EC, for Utilities Contracts; and

- Directive 2014/23/EU on the award of concession contracts, which does not directly replace any previous directive.

Contracting authorities and entities to whom these directives apply include all central UK Government Departments and Agencies including both Houses of Parliament, HM Treasury, the Cabinet Office, Ministry of Justice and all courts, Ministry of Defence, Department of Health and the Department of Communities and Local Government. A more detailed list may be found within the Annexes to Commission Decision 2008/963/EC.

The EU Commission also claim that these new rules ensure that the award of contracts of higher value for the provision of public goods and services must be fair, equitable, transparent and non-discriminatory. We now know that this reflects the language used in UN General Assembly resolution 66/95 of 2011.

The Lisbon Treaty, which was signed by member states on 13 December 2007 and came into force on the 1st December 2009, gave the European Union the legal personality to enter into international agreements on behalf of it member states. The European Union, with regard to its 28 member states, including the United Kingdom, acceded to the GP Agreement on 6 Apr 2014. The main provisions of this WTO agreement appear to have been cascaded down to all EU member states in the form of the EU Directives we have already briefly examined above.

Transposing Procurement Rules Into UK Law

According to this document, published by the Cabinet Office, there has been "a long running period of continuous UK stakeholder engagement on the new EU Public Sector Directive, which started in 2011 when the European Commission’s own consultations began".

A short Consultation on the Draft UK Public Procurement Regulation was published by the Government on the 19th September 2014 and closed on 17 October 2014. A link to this final consultation "was issued directly to a number of known stakeholders and was also made available publicly on the GOV.UK website". Unsurprisingly, it received just 200 responses. We believe that the process of transposing the EU Directives into UK law resulted in a 'copy-out approach' being employed in the absence of 'gold-plating'. We have also noted that many respondents to the final consultation remarked that that there was "helpful alignment between EU Directive article number and regulation number" - in other words it was a simple 'copy and paste' job.

The EU Procurement Directives became transposed into UK Law by the Minister for the Cabinet Office making Statutory Instruments (Regulations) under delegated powers found within section 2(2) of the European Communities Act 1972. The procedure for making Statutory Instruments often means that they become law without either a debate or a vote in Parliament.

The relevant Regulations are the Public Contracts Regulations 2015 and the Utilities Contracts Regulations 2016 which come into force between 26th February 2015 and 18th October 2018. The Concession Contracts Regulations 2016 came into force on 18th April 2016. We understand that certain exemptions might apply to buyers working within the defence and security sector, where requirements may be covered by the earlier Defence and Security Public Contracts Regulations (DSPCR) 2011.

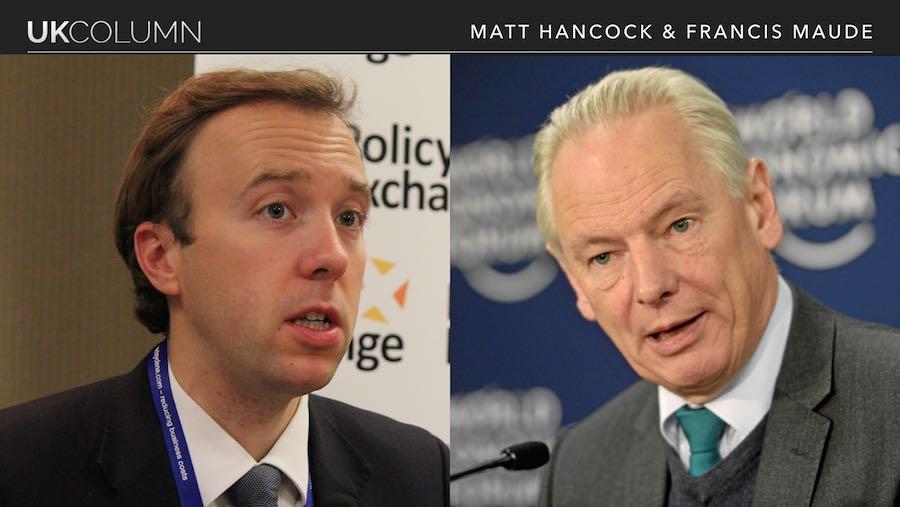

The Minister for the Cabinet Office at the time of the making of the Public Contracts Regulations was Francis Maude. The 2016 Regulations were made when Matthew Hancock was Minister.

The policies and regulations governing public sector procurement are many and we have now seen how they have been shaped and influenced at the International and regional levels. An idea of their complexity and the depth and breadth of their reach can be discovered here.

The fact that this raft of UK Procurement Regulations came into effect so close to the enactment of the European Union Referendum Act 2015 defies belief.

The Practical Effect Of Procurement Rules Within The UK

Examples of the impact of these Global Procurement Rules are not difficult to find.

The Conservatives faced heavy criticism in 2011 after German manufacturing giant Siemens secured a £1.6billion contract to provide new train carriages for the Thameslink route. The Munich-based company fought off competition from Bombardier, which operates the UK’s last remaining train factory in Derby. In order to deflect criticism of itself the Government website states that "the competition to supply trains and maintenance services for the Thameslink programme was designed and launched under the previous administration in 2008, in accordance with EU procurement procedures".

In 2012 a £452m contract to build four new fuel tankers to supply the Royal Navy was awarded to a firm in South Korea. The MoD’s procurement chief Bernard Gray is reported to have said, "the competition for the contract sought to engage shipbuilders from across the globe ...".

In 2013 it was revealed that the Government had been planning to outsource to the private sector the responsibility for buying £14bn of equipment each year. The plan, heavily criticised in a report by the Royal United Services Institute, had been to establish a government owned contractor operated group (GOCO) and outsource more than 40% of the MOD budget. Of the groups bidding for the right to run the MOD's defence equipment and support (DE&S) one consisted of the US engineering firm CH2M Hill, WS Atkins, and Serco. The other group comprised the US engineers Bechtel, PriceWaterhouseCoopers, and PA Consulting. By December 2013 it was announced that plans to privatise defence procurement were to be 'scrapped'.

In January 2014 we learned a the farcical story of the MOD buying back HMS Ark Royal parts so that HMS Illustrious, which had been damaged by a fire, could be repaired. Britain had decommissioned and sold the ageing Ark Royal for £2.9 million to Turkey. 14 other Navy vessels, including aircraft carrier Invincible, have been scrapped by Turkish shipyard Leyal Gemi Sokum since 2008.

In 2015, at the time of the NATO summit in Newport South Wales, David Cameron made headlines by announcing a £3.5 bn order for specialist scout vehicles for the army. It was later learned that 40% of the work was to be completed by overseas firms - £1.4 bn of contracts were therefore lost to British owned firms. That same report mentioned that "£75million of army uniform production was outsourced to India, China and Eastern Europe".

South Wales based firm, Swansea Dry Dock Ltd, was fighting last year to win a contract to re-cycle the unwanted type 42 destroyers HMS Edinburgh, HMS Gloucester and HMS York. When SDC pointed out to the MoD that it could not compete with the lower labour costs and less onerous environmental regulations in non-EU countries the MoD replied that it was bound by the principles of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) and "could not discriminate on grounds of nationality and must treat all competitors equally".

On 30th June 2016 John Speller MP asked the Minister for the Cabinet Office if he "will take steps to ensure that his Department's purchasing policies support British (a) industry and (b) agriculture". The written response was that "the Government is committed to doing all it can to ensure UK suppliers can compete effectively for public sector contracts in line with our current international obligations ... We are providing industry with visibility of up to £191bn of potential procurement opportunities across 19 sectors". Omitted in the Minister's answer is the requirement that the international obligations prevent "buy national" purchasing policies.

In the past decade we have also seen privatisation of segments of the Prison Service involving global corporations such as SERCO and CAPITA. It would be difficult to dispute the fact that these International Public Procurement rules have led to the situation were the public no longer know who really runs the public sector.

Following the EU Referendum vote it is difficult to see how these International Public Procurement rules can be ignored by future British Parliaments wishing to develop "buy national" public procurement policies and promising to provide "British jobs for British workers". International Public Procurement rules lay bare the lies of Brexit, and it is clear that the greatest threat to the United Kingdom regaining its place as a fully independent, sovereign Nation is the ongoing rise of Global Governance.