Recent persecution and prosecution for dissent and protest, beginning with doctors and other professionals losing their careers for questioning public health policy, has led many to ask questions about what if any constitutional rights we have in the United Kingdom to freedom of speech.

A proper analysis leads to the surprising conclusion that not only did the UK have the First Amendment before the USA did, but that it still has it; and that British constitutional law regarding the right to freedom of speech is stronger in many respects than even the US Constitution, indicating a broader Anglo-American exceptionalism in this respect. All that we have to do, therefore, is to learn our ancient rights and then preserve, protect and defend them.

The most important part of the First Amendment to the US Constitution (part of the US Bill of Rights) is the Petitioning Clause, emphasised in bold below together with the relevant syntax from the foregoing clauses of the First Amendment:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Thus: Congress (the US parliament) shall make no law abridging the right of the people to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

The Petitioning Clause is of the greatest importance because the majority, if not all, of speech under threat is speech that is critical of government or speech that the Government frowns upon. Other free speech is rarely, if ever, at any threat from Congress or Parliament.

Many claim that the USA is unique in this respect, but the British Isles had the First Amendment first and they still have it, alongside the Commonwealth Realms of Canada, Australia and New Zealand and also the Republic of Ireland, where the 1688 English Bill of Rights continues to be on the statute books.

The Petitioning Clause of the First Amendment was no innovation in 1789. It is an amalgam of Articles 5 and 13 of the 1688 English Bill of Rights and Articles 23, 24 and 25 of Scotland’s 1689 Claim of Right. The subjects' immunities of both the English Bill and the Scottish Claim of Right apply to the whole of the UK by virtue of the Acts of Union (Art. 4 Union with Scotland Act 1706; Art. 4 Union with England Act 1707; Art. 6 Union with Ireland Act 1800; Art. 6 Act of Union (Ireland) 1800 and pursuant to Calvin's Case). These combine to provide greater protection than even the US First Amendment in many respects; but Americans need not fear, because any additional rights are supposed to apply in the USA by virtue of the Ninth Amendment, which retained any Colonial subjects' rights that pre-dated the formation of the United States of America.

These constitutional laws were consented to by the respective English and Scottish Convention Parliaments—constitutional conventions assembling when there was no Parliament sitting in either realm—after King James II (VII in Scotland) had departed the Crown. They they were then presented as conditions for the British realms accepting William III as King. Both are structured with a list of grievances against King James, the Heads of Declaration, followed by a list of Subjects’ Rights that King William III was charged with protecting as head of state, much as the US President swears an oath to uphold the Constitution.

1688 Bill of Rights

Heads of Declaration: Whereas the late King James the Second, by the Assistance of diverse evill Councellors Judges and Ministers imployed by him, did endeavour to subvert and extirpate the Protestant Religion and the Lawes and Liberties of this Kingdome […] By Committing and Prosecuting diverse Worthy Prelates for humbly Petitioning to be excused from Concurring to the said Assumed Power.

Art. 5: That it is the Right of the Subjects to petition the King, and all Commitments [to jail] and Prosecutions for such Petitioning are Illegall.

Art. 13: And that for Redresse of all Grievances and for the amending strengthening and preserveing of the Lawes, Parlyaments ought to be held frequently.

“The Right of the Subjects to petition the King” means the same thing as the US Bill of Rights’ phrase “the right of the people to petition the Government”, because the British Government is the King’s government, known formally as His Majesty’s or HM Government. (The 1708 edition of the Collins Dictionary confirms the definition of the word petition at the time of the Glorious Revolution of 1688. It defines petition, as a noun, as “a Supplication or Request made by an Inferiour to a Superior”, with supplication being “the action of asking or begging for something earnestly or humbly.”) This subject's right should be considered to extend to all branches of government, including legislatures both national and local, courts, juries and executive officials and agencies. This includes public employers, public university systems, and state school systems; and could be considered to extend to private organisations and individuals benefiting from public money.

Whilst no express mention is made in the Bill of Rights of Parliament being prohibited from making any law abridging the right to petition (in the manner made explicit in the US Bill of Rights), this is an implied clause that should render any statute, statutory instrument, policy or application of statute by the British Government ultra vires to the extent that it unlawfully restrains the right to petition.

The Heads of Declaration then help to clarify that petitioning the King means requesting to be excused from agreeing with or complying with the King and his Government and courts. The adverb “humbly”, qualifying the scope of the action, means that a petitioner may nonetheless not obstruct any lawful activities of the Government. Use of the term “subject” then confirms that the right to petition is enjoyed by anybody who is governed by HM Government regardless of citizenship, this being analogous to “the people” in the First Amendment.

The English Bill of Rights goes much further than the US Constitution by expressly stating that “all Commitments [to jail] and Prosecutions for such Petitioning are Illegall”—they are a criminal offence. At the time, a commitment meant the “action of officially consigning to the custody of the state,” i.e., being arrested, remanded in custody, put on bail or imprisoned. (This sense lingers in the idiom being committed to an institution.)

This provision is unlike the US First Amendment, which only touches on civil tort law. That is, Americans can only sue, not prosecute, authorities for a breach of their constitutional rights because the US Constitution does not make constitutional violations by government a criminal offence. The clause of the English Bill of Rights that we are considering here is a particularly powerful plank of our Constitution because it implies that police can be prosecuted for arresting and holding a person and that prosecutors can be pursued criminally for prosecuting charges and that a judge can be prosecuted for sentencing a person for exercising their right to petition. As Americans often remind us, their founders put the First Amendment first in the Bill of Rights—even ahead of the right to keep and bear arms—for good reason.

Also, regarding related civil claims, awards of exemplary (or punitive) damages may, according to the current tribunal law of England and Wales, be made against public officials who have acted in an “oppressive, arbitrary or unconstitutional way”. This really ought always to be the case in the USA regarding violations of the Constitution; see Rookes v Barnard (1964) AC 1129, p. 38. Since the Law Lords were acting in that case as the supreme court of a common-law jurisdiction, there is a presumption of comity (mutual respect of this verdict) by the supreme courts of the USA and Commonwealth nations.

Article 13 of the Bill of Rights 1688 then implies a British subject's right to petition both houses of Parliament by stating that “Parlyaments ought to be held frequently […] for Redresse of all Grievances”. Of course, grievances can only be redressed if there is a cognate right to freedom of speech regarding grievance. This clause elevates the expression of any grievance to the status of constitutionally protected speech. After all, such freedom of speech is necessary for the proper functioning of democracy. In referring to all grievances, the English Bill of Rights uses stronger terms than the US First Amendment, which refers to grievances without specification of type, leaving the door open for the extent of these constitutionally protected grievances to be whittled down in subsequent jurisprudence.

Blackstone later clarified this point about the right to petition both King and Parliament for redress of grievances, stating that “there still remains a right appertaining to every individual, namely, the right of petitioning the king, or either house of parliament, for the redress of grievances.”

Article 13 further sets out that the way that Parliament can redress grievances is by “the amending strengthening and preserveing of the Lawes”, thereby implying that the constitutional right to freedom of speech extends to expressing all and every grievance in the context of petitioning that the law be amended, strengthened or preserved. It is therefore unlawful for any UK statute law to prevent the raising of grievances; and any law, regardless of how virtuous it may appear when being pitched by the authorities, cannot be above criticism.

This distinction between petitioning HM Government and petitioning Parliament in the English Bill of Rights is helpful because it clarifies quite correctly that humble petitioning of the King (in this case, the executive and judiciary) relates to requesting, without making uproar, to be excused from complying with government and with sentences handed down by the courts.

Street protests

Whereas the English Bill of Rights is silent on the right to peaceably assemble, this right is nonetheless implied. As set out by A.V. Dicey in Chapter 7 (“The Right of Public Meeting”) of his authoritative Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution (1915), the right of assembling in English law is “nothing more than a result of the view taken by the courts as to individual liberty of person and individual liberty of speech.” He amplifies, in terms which lay bare the lawlessness of contemporary executive practices such as dispersal orders and other blanket bans on the right of assembly and free association:

There is no special law allowing A, B, and C to meet together either in the open air or elsewhere for a lawful purpose, but the right of A to go where he pleases so that he does not commit a trespass, and to say what he likes to B so that his talk is not libellous or seditious, the right of B to do the like, and the existence of the same rights of C, D, E, and F, and so on ad infinitum, lead to the consequence that A, B, C, D, and a thousand or ten thousand other persons, may (as a general rule) meet together in any place where otherwise they each have a right to be for a lawful purpose and in a lawful manner.

In 1619, Lambard stated the basic common law attitude as regards the act of assembly in England:

An unlawful assembly is of the companie of three or more persons, disorderly coming together, forcibly to commit an unlawful act, as to beat a man or to enter upon his possession or the like.

One such unlawful act that will scupper otherwise peaceful assembly, often encouraged by agents provocateurs to encourage unnecessary clashes with the police, is obstruction of a highway without lawful excuse; an offence that is found as far back as the pre-Conquest laws of Edward the Confessor, which set out the duty of the King to maintain free passage on the King’s highways and waterways.

This offence occurs despite an assembly otherwise being lawful, when “[a]ny unreasonable or excessive use of a highway or activity on or near the highway which renders the highway less commodious to the public is enough to constitute a nuisance” (Lowdens v Keaveney [1903] 2 IR 82). This generally contrasts with a lawful procession, where protestors march at a reasonable pace on a highway, exercising their right of passage without unduly interfering with the rights of other road users.

The UK Supreme Court did, however, recognise in DPP v Ziegler (UKSC 2019/0106) that obstruction of a highway can be lawful in the context of otherwise peaceful protest within the narrow confines of a four-stage test of proportionality. It is of such a limited scope that protestors would be well advised to liaise with police in advance of exercising this limited right:

- (i) Is the aim sufficiently important to justify interference with a fundamental right?

- (ii) Is there a rational connection between the means chosen and the aim in view?

- (iii) Was there a less intrusive measure which could have been used without compromising the achievement of that aim?

- (iv) Has a fair balance been struck between the rights of the individual and the general interest of the community, including the rights of others?

Two places in the UK—both in Westminster—that have special laws regarding assembly are Parliament Square and Trafalgar Square. Section 380(7)(b) of the Greater London Authority Act (1999) states that a determination as to whether to permit a public demonstration to take place may only be made by the Deputy Mayor of London or a member of staff of the Authority, which can only occur in accordance with the local by-laws that they enforce. It is not therefore for the Metropolitan Police to make such a call as to whether an assembly is peaceful, because the Metropolitan Police operate under the Mayor rather than the Deputy Mayor of London.

When it was pointed out in Westminster Magistrates’ Court towards the end of lockdown that the Coronavirus Act did not—for the above reason—apply to these places regarding assembly, Trafalgar Square was mysteriously fenced off for a period of time. It is notable that mounted police only dispersed protestors from the top of Trafalgar Square in front of the National Gallery, likely because that part of the square continues to be a pedestrian highway that the police have a duty to keep clear of protestors.

Another common problem with peaceful assembly is agitation by disruptive counter-protestors, which the courts have traditionally and rightly frowned upon. In Beatty v Gillbanks (Queen’s Bench Division, 13 June 1882), it was found that persons who are lawfully and peaceably assembled, in that case Salvationists, could not be convicted of the offence that they did “unlawfully and tumultuously assemble with divers other persons […] to the disturbance of the public peace” where the evidence showed that the disturbances were caused by other people antagonistic to the cause.

More recently, in confirmation of the legal principle that protestors cannot be removed by resorting to blaming them for bystanders’ unlawful acts, in Redmond-Bate v. DPP (1999) EWHC Admin 733, the High Court of England and Wales ruled that preachers outside Wakefield Cathedral did not cause a mob protesting against them to breach the peace and that West Yorkshire Police arrested the wrong people by arresting the three preachers.

It is now routinely asserted by police across the United Kingdom, as if it were self-evident, that preachers and evangelists have to be arrested or removed from the scene where passersby threaten to riot in response to their message. Scots law in particular is notoriously draconian in allowing police to arrest anyone speaking loudly on the street for a supposed breach of the peace. Yet the above case-law confirms that the police duty in such cases is to keep the King’s peace by physically protecting the preacher’s freedom of speech.

Scottish Claim of Right

Art. 23: That it is the right and priviledge of the subjects to protest for remeed of law to the King and Parliament against Sentences pronounced by the lords of Sessione, Provydeing the same do not stop Execution of these sentences.

Art. 24: That it is the right of the subjects to petition the King and that all Imprisonments and prosecutiones for such petitioning are Contrary to law.

Art. 25: That for redress of all greivances and for the amending, stren[g]thening and preserveing of the lawes, Parliaments ought to be frequently called and allowed to sit, and the freedom of speech and debate secured to the members.

Article 23 is a helpful clause in addition to what we find in the English Bill of Rights. It refers expressly to the right to petition regarding sentences handed down by the courts, with the term “humbly”—found in the English Article 5 as discusssed above—expanded in this Scottish clause to confirm that one may not, despite his petitions, “stop Execution of these sentences”. This clause puts into serious question various reporting restrictions on court cases—in particular, regarding the recent judicial innovations of "family courts" and the "Court of Protection"—which often arbitrarily impose reporting restrictions that unconstitutionally suspend all rights to petition.

The Scottish Claim of Right is otherwise similar to the English Bill of Rights in this respect.

The English Bill of Rights also has a General Savings Clause—with similar provisions in the Scottish Claim of Right—which requires these rights to be maintained “in all times to come”. Therefore, any contemporary statute, statutory instrument, policy, or claimed obligation upon government under international law that unlawfully restrains the right to petition should in theory be treated as void and ultra vires insofar as it restrains the right to petition.

What this means is that Parliament cannot outlaw criticism of the Government and cannot lawfully restrain the right of the people to petition Parliament (as distinct from petitioning the King) for the redress of all grievances and regarding petitions to amend, strengthen and preserve the law. The English Bill of Rights reconfirms the inalienable constitutional rights of subjects:

That all and singular the Rights and Liberties asserted and claimed in the said Declaration are the true auntient and indubitable Rights and Liberties of the People of this Kingdome and soe shall be esteemed allowed adjudged deemed and taken to be,

and that all and every the particulars aforesaid shall be firmly and strictly holden and observed as they are expressed in the said Declaration,

And all Officers and Ministers whatsoever shall serve their Majestyes and their Successors according to the same in all times to come.

The Prince of Orange’s Declaration of Reason

The right to petition and the context for it being incorporated into a bill of rights is explained in further detail in the most overlooked of the constitutional documents of the 1688 revolution, the Prince of Orange’s (the future King William III’s) Declaration of the Reasons inducing him to appear in Arms in the Kingdom of England, for preserving of the Protestant Religion, and for restoring the Laws and Liberties of England, Scotland, Ireland (19 December 1688, Journal of the House of Commons: Volume 10, 1688–1693).

The Prince, in what could be considered the Declaration of Independence or Act of Abjuration of the British realms, had the following to say about the right to petition (emphasis added), in reviewing the abuses of the short and disastrous reign of James VII/II that had prompted him to accept the call to come over from the Netherlands:

Those great and insufferable Oppressions, and the open Contempt of all Law, together with the Apprehensions of the sad Consequences that must certainly follow upon it, have put the Subjects under great and just Fears, and have made them look after such lawful Remedies as are allowed of in all Nations: Yet all has been without Effect. And those evil Counsellors have endeavoured to make all Men to apprehend the Loss of their Lives, Liberties, Honours and Estates, if they should go about to preserve themselves from this Oppression by Petitions, Representations, or other Means authorized by Law.

Thus did they proceed with the Archbishop of Canterbury, and the other Bishops; who, having offered a most humble Petition to the King, in Terms full of Respect, and not exceeding the Number limited by Law, (in which they set forth, in short, the Reasons for which they could not obey that Order, which by the Instigation of those evil Counsellors was sent them, requiring them to appoint their Clergy to read in their Churches the Declaration for Liberty of Conscience) were sent to Prison, and afterwards brought to a Trial, as if they had been guilty of some enormous Crime. They were not only obliged to defend themselves in that Pursuit, but to appear before professed Papists, who had not taken the Test, and by consequence were Men whose Interest led them to condemn them: And the Judges that gave their Opinions in their Favours were thereupon turned out.

And yet it cannot be pretended, that any Kings, how great soever their Power has been, and how arbitrary and despotick soever they have been in the Exercise of it, have ever reckoned it a Crime for their Subjects to come, in all Submission and Respect, and in a due Number not exceeding the Limits of the Law, and represent to them the Reasons that made it impossible for them to obey their Orders. Those evil Counsellors have also treated a Peer of the Realm as a Criminal, only because he said that the Subjects were not bound to obey the Orders of a Popish Justice of Peace; though it is evident, that, they being by Law rendered incapable of all such Trust, no Regard is due to their Orders; this being the Security, which the People have by the Law, for their Lives, Liberties, Honours and Estates, that they are not to be subjected to the arbitrary Proceedings of Papists, that are, contrary to Law, put into any Employments Civil or Military.

It is legitimate for the Prince to have used the strong language in his declaration, found in the Journal of the English Parliament, so as to provide context in a court of law to the right to petition. These powerful words make it abundantly clear that restraint of the right to petition is unspeakably arbitrary and despotic and that there is no honest way to pretend that any restraint of it could ever in any way be considered reasonable.

The Trial of the Seven Bishops

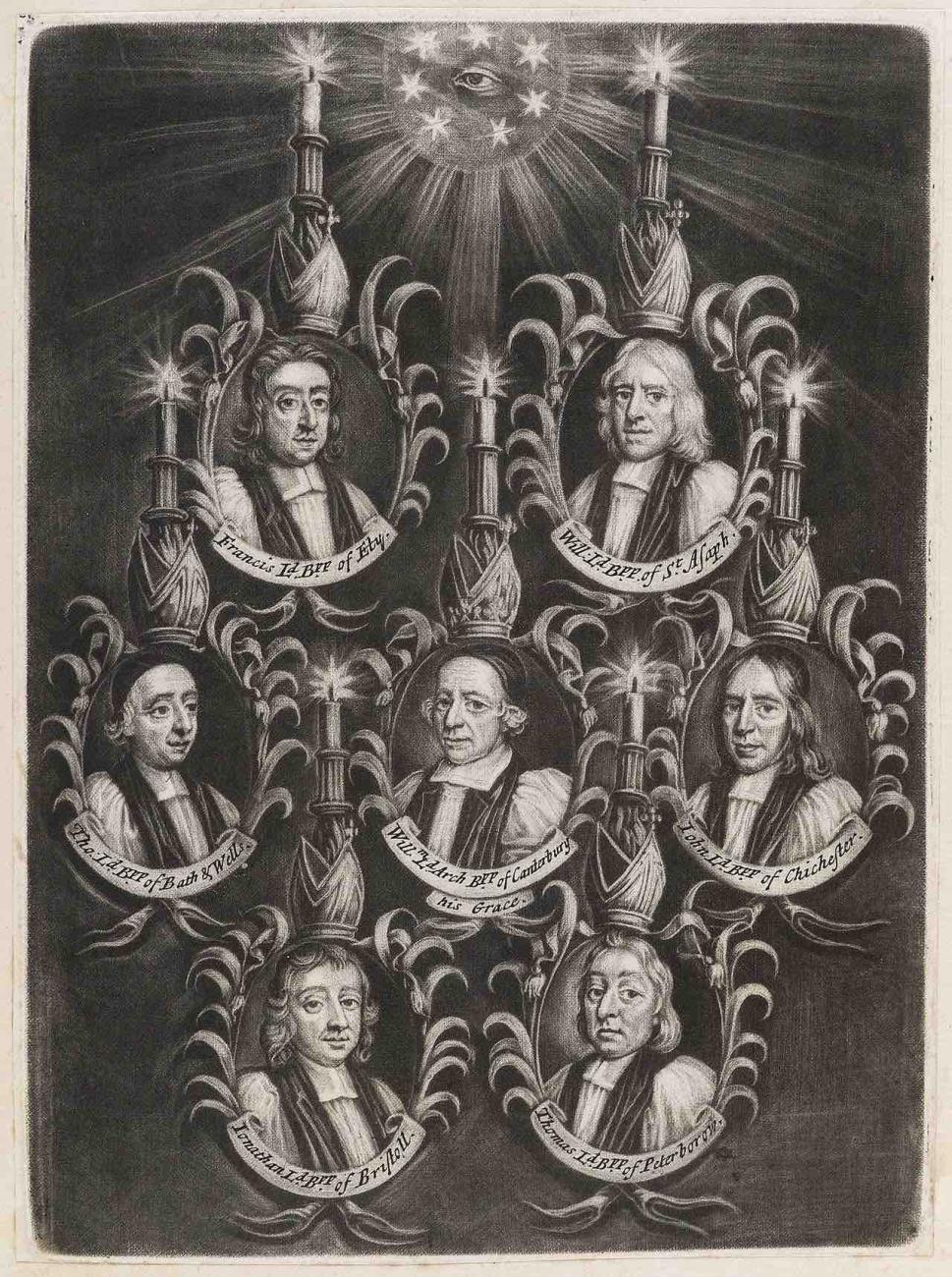

In his Declaration of Reason, William refers to arguably the most important constitutional case in Anglo-American and Commonwealth history, one that should be required reading for all legal students and which used to be common knowledge among schoolchildren: the Trial of the Seven Bishops. These seven are the Prelates referred to in the Bill of Rights, comprising the Archbishop of Canterbury and six of the other Bishops (Lords Spiritual) with a seat in the House of Lords.

The Seven Bishops persecuted in James VII/II's reign. (Public domain)

The seven Bishops were “imprisoned” in the Tower of London by the King without him “expressing the reasone” and with the King “delaying to put them to tryall”, to quote the expression of this grievance in the Scottish Claim of Right.

This was until they were liberated by a writ of Habeas Corpus to stand trial in the Great Hall of Westminster for what was to prove the trial of the century. There, the Bishops were accused by the Crown of committing seditious libel but were subsequently acquitted by the jury, against the direction of the judges, in the most dramatic of circumstances, because they had exercised their “true, auntient and indubitable” right to petition the King and Parliament in the public square and via the printing press.

Freedom of the press

Freedom of the press, expressly referred to in the US First Amendment, is confirmed for the United Kingdom in the proceedings of the trial of the Seven Bishops. The transcript contains much debate over the publishing of the petition in Middlesex (the county around London) and it being distributed nationwide by means of the printing press. Whereas the Crown—in a typical attempt at denial of constitutional rights by scope-narrowing—claimed that the Bishops only had a right to present their petition in Parliament or to the King in person, it was found by the highest court in the land that the right did extend to the freedom to publish their petition widely.

It is also abundantly clear that any abridgement of the freedom of the press regarding the right to petition would result in unlawful restraint of the right to petition. This must be considered today to extend to electronic communications, which for a growing majority of people form the primary means of expression. It is therefore implied that Parliament may constitutionally make no law abridging the freedom of the press and the freedom of social media, etc., insofar as such restrains the right to petition.

The right of the press has, however, never extended to slanderous news that may cause discord. Article 34, “Of slanderous Reports”, of the 1275 First Statute of Westminster did, for example, provide, on the pain of imprisonment,

That from henceforth none be so hardy to tell or publish any false News or Tales whereby discord occasion of discord or slander may grow between the King and his People, or the Great Men of the Realm.

1661 Tumultuous Petitioning Act

The above mention by Prince (later King) William III to “a due Number not exceeding the Limits of the Law” referred to the limits on the right to petition Parliament set out in the 1661 Tumultuous Petitioning Act (13 Car. II. st. 1. c. 5), in which the government and parliament of the day—while reconfirming the pre-existing English right to petition—sought to limit the act of “presenting publick Peticions or other Addresses to His Majesty or the Parliament” to groups of ten people, with a maximum number of twenty being allowed to sign any such petition. These limits, imposed soon after the restoration of the monarchy in an attempt to prevent a repetition of the tumultuous opening of the Long Parliament of England's republican years (1640–1660), were rendered void by the Bill of Rights, which prohibits prosecutions and commitments for “all such petitioning”.

Whilst these arbitrary limits on assembly in the 1661 Act can be disregarded entirely following 1688, the Act was discussed at length in the Trial of the Seven Bishops as evidence of the right to petition. The 1661 Act does, therefore, provide useful context to what the men of the Glorious Revolution meant when they referred to the right to petition. It also demonstrates that, as in the USA, there is only a right to assemble peaceably, not tumultuously. There has never been any right to riot anywhere in the British Isles. For example, the Riot Act allowed authorities to declare that a group of twelve or more had unlawfully assembled but they would be given an hour to disperse following a riot proclamation ("reading the Riot Act")—unlike today, where sometimes peaceful protestors will be "kettled" (a forceful intervention) without warning.

The 1661 Act begins with reference to petitions, complaints, remonstrances (meaning an earnest presentation of reasons for opposition or grievance) and declarations and other addresses to the King, or to both or either Houses of Parliament, for alteration of matters established by Law; the redress of grievances in Church or State; or other public concerns. This does parallel, and provides context to, that right to petition which is reflected in the US First Amendment.

The Act also provides important context to the right of a Member of Parliament to petition the King, referring to the MP’s cognate right to “enjoye theire freedome of Accesse to His Majesty as heretofore hath beene used”. This means that it is the right of an MP to have access to the King’s Secretaries of State and Prime Minister, “for Redresse of all Grievances and for the amending, strengthening and preserveing of the Lawes”, with the people likewise having a right to freedom of of access to their local MP for the same. The growing restrictions on personal meetings at constituency "surgeries", and the tendency for ministers to be unavailable to "ordinary" MPs, are thus unconstitutional.

1998 Human Rights Act

While it may seem archaic to rely on these ancient constitutional laws and customs, and tempting to rely on Tony Blair’s 1998 Human Rights Act (which pays lip service to the rights of expression, assembly and association), it is important to recognise that—in contrast to traditional Anglo-American individual rights—"human rights" are communitarian in nature. This is done by curtailing individual rights by purported duties (the "balancing of rights with responsibilities") to produce an alleged “community” that is ultimately defined by the Establishment.

For example, the Article 10 right to freedom of expression and Article 11 right to freedom of assembly and association in the Human Rights Act (transpositions into UK law of the same articles in the much older European Convention on Human Rights) sound wonderful—until you read subsection 2 of each, which allows the right to be suspended, subject to arbitrary

formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society.

These purported rights can also be arbitrarily suspended

in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, etc.

The way that "human rights" are constructed results in individual rights being set against duties to the community, in a Maoist-style struggle session, until your individual rights are overcome when that is the goal of the state. In contrast, the right to petition, and the associated implied right to assembly and association for the same found in the Bill of Rights and Claim of Right and the US First Amendment, are set out as fundamental, inalienable, individual rights that cannot be arbitrarily suspended by government.

US Supreme Court

With the right to petition in the UK and Commonwealth being almost perfectly aligned with the US First Amendment, and with there being little in the way of case law outside of the USA regarding it, we would be well served to refer to US Supreme Court rulings on the First Amendment in order to be informed on how it should be interpreted by the British courts, if we shall decide to rely on these ancient rights in place of Tony Blair’s 1998 Human Rights Act and the ECHR.

The opinion of the US Supreme Court in Borough of Duryea v. Guarnieri (564 U.S. 379, 2010) assists with the definition of a petition. It states, referencing Sure-Tan Inc. v. NLRB (467 U.S. 883, 896–897, 1984), that “[i]nterpretation of the Petition Clause must be guided by the objectives and aspirations that underlie the right. A petition conveys the special concerns of its author to the government and, in its usual form, requests action by the government to address those concerns.”

The US Supreme Court has stated that the right to freedom of speech and the right to petition are "cognate rights", indicating that a right to petition implies a general right to freedom of speech, this similarly being implied by the English Bill of Rights and Scottish Claim of Right. In 1945, in Thomas v. Collins (323 U.S. 516, 530), the Court stated:

It is therefore in our tradition to allow the widest room for discussion, the narrowest range for its restriction, particularly when this right is exercised in conjunction with peaceable assembly. It was not by accident or coincidence that the rights to freedom in speech and press were coupled in a single guaranty with the rights of the people peaceably to assemble and to petition for redress of grievances. All these, though not identical, are inseparable. They are cognate rights […] and therefore are united in the First Amendment’s assurance.

The US Supreme Court has also ruled that the First Amendment protects the right to association for freedom of expression for expressive purposes, often for political purposes, without undue state interference.

American jurisprudence is particularly informative regarding how the right to petition should protect employees—notably from the public sector and public service careers, such as those of lawyer and teacher, that are government-regulated—who speak out about public policy. Many have lost their jobs for questioning, for example, pandemic vaccine policy; speech that should be afforded constitutional protection.

Pickering v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 563 (1968), is especially useful in this regard. It relates to a teacher who was dismissed for criticising in a letter to a newspaper the school board that employed him. The Court held that, in the absence of proof of the teacher ”knowingly or recklessly” making false statements, he had a right to speak on issues of public importance without being dismissed from his position.

It was found in this case that public employees do not relinquish their right to petition, i.e. to speak out on matters of public importance or public concern, merely because they have accepted government employment or employment in a government-regulated public service career. In the half-century since this ruling, the proportion of people employed in government-regulated professions or the public sector has of course grown greatly in all Western countries.

Justice Thurgood Marshall, writing for the majority, also observed that

the problem in any case is to arrive at a balance between the interests of the teacher, as a citizen, in commenting upon matters of public concern and the interest of the State, as an employer, in promoting the efficiency of the public services it performs through its employees.

In 1983, the US Supreme Court clarified the balancing that must be done in such cases—in Connick v. Myers (Connick, District Attorney in and for the Parish of Orleans, Louisiana v. Myers, 461 U.S. 138, 1982), forming what is referred to as the Pickering-Connick test. The test has two prongs:

- The threshold prong asks whether a public employee spoke on a matter of public concern defined as a matter of larger societal significance or importance. If a public employee was disciplined for expression that is characterised as more of a private grievance that is more properly dealt with by their employer’s grievance procedures and employment tribunal, then the employer prevails;

- If, however, a public employee spoke on a matter of public concern, then the court proceeds to the second prong of the test, often called the balancing prong. Under this test, the court must balance the employee’s right to free speech against the employer’s interests in an efficient, disruptive-free workplace.

It was found that the right to petition outweighed the employer’s interests because the employee, in the role of respondent in this case, had not publicly criticised the people with whom she worked on a daily basis, with her speech focussing on matters of public rather than private employment interest.

In Garcetti v. Ceballos (547 U.S. 410, 2006), the Court introduced a new threshold for the balancing prong, by holding that when public employees make statements pursuant to their official job duties, without raising issues of public importance, they have no First Amendment protections.

Finally, in the aforementioned Borough of Duryea v. Guarnieri (564 U.S. 379, 2010), the Court found that public employees must show that they spoke as a citizen on a matter of public concern when suing their employer under the First Amendment's Free Speech or Petition Clauses.

A better understanding of the right of public and civil service employees—and perhaps also private employees—to contribute to public debate on matters of public interest would transform public debate in Britain and the Commonwealth, preventing the silencing of dissent that inevitably leads to calamities in public policy. For we surely cannot achieve a vibrant public debate and a healthy, sustainable democracy if the government, regulators, media, employers and other institutions that people contractually rely on proceed to unreasonably silence professionals—the very experts whose voice is necessary for sound public policy—on the pain of them apprehending, to quote the Prince of Orange,

the Loss of their Lives, Liberties, Honours and Estates, if they should go about to preserve themselves from this Oppression by Petitions, Representations, or other Means authorized by Law.

The right to petition is indeed ancient

Further context can be given to furnish proof that the right to petition is truly ancient, as was already asserted over three hundred years ago in England’s 1688 Bill of Rights and Scotland’s 1689 Claim of Right. William Stubbs explains that Edward the Confessor’s pre-Conquest Parliament would deliberate on petitions delivered and filed in the order in which they had been received, with the status of the petitioner not being relevant, thus indicating that the right which MPs had of access to the King was equally applied regardless of status.

It was customary then that Parliament was not dismissed so long as any petition remained undiscussed; or, at least, any to which the reply had not been determined on. The King could be found guilty of contempt of Parliament [a form of perjury] if he permitted the contrary.

— The Manner of Holding Parliament (Stubbs' "Charters," p. 502)

Following the Norman Conquest, Article 61 Magna Carta (1215) was an early reassertion of the rights that Barons previously had to redress of grievances from the King.

Chapter 5 of the First Statute of Edward III (1340) then put petitioning on a formal statutory footing. It required that a Commission be provided at every Parliament to

hear by petition delivered to them, the Complaints of all those that will complain them of such Delays or Grievances done to them […] because divers[e] Mischiefs have happened, for that [= since] in divers Places—as well in the Chancery as in the King’s Bench, the Common Bench, and in the Exchequer, before Justices assigned, and other Justices to hear and determine disputed—the Judgements have been delayed, sometimes by Difficulty, and sometimes by divers[e] Opinions of the Judges, and sometime for some other Cause.

Because such various "mischiefs" will continue to occur, the ancient fundamental constitutional right to petition must be preserved, protected and defended.

Remedy: A British and Commonwealth First Amendment

These ancient rights could be translated into a UK and Commonwealth First Amendment that may read as follows:

Parliament shall consent to no law abridging the right of the people to petition their King and his Government or to petition both Houses of Parliament for a redress of any grievance and for the amending, strengthening and preserving of the Laws in Church or State, or other public concerns, or regarding sentences pronounced by the King’s courts or delays thereof; nor of the cognate freedom of speech, or of the press; nor of the right of the people to associate and peaceably assemble; nor the right of the Members of both Houses of Parliament of freedom of access to His Majesty and his Secretaries of State; nor the right of the people of freedom of access to their Members of Parliament; and all detentions, bails, fines, forfeitures, interdictions and prosecutions for such petitioning are illegal.

Main image: Hemming-in of free speech on Parliament Square, 2010 | John W. Schulze | licence CC BY 2.0